Ever since the advent of rock and roll and the vinyl record explosion in the 50s, record companies – whose business is making money – have been using music in order to meet that aim.

Ever since the advent of rock and roll and the vinyl record explosion in the 50s, record companies – whose business is making money – have been using music in order to meet that aim.

Whatever musicians managed to talk themselves into believing regarding the altruistic motives of the record company moguls who schmoozed them, the bottom line was always ‘make money or get the hell out‘. And tough luck if the music you love to make goes out of fashion – you’d better change. After all, there are bills to be paid. Your contract says so.

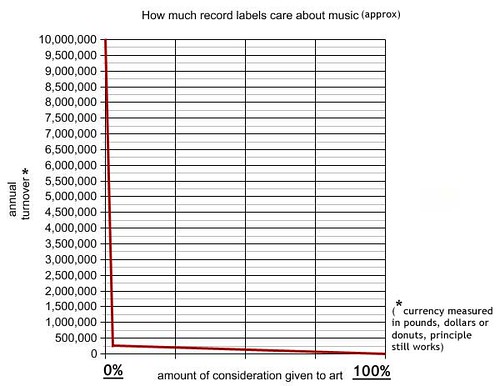

The size of the record label has almost always been in strict inverse proportion to their interest in “unfettered music”:

And so many of the discussions ‘the industry’ are having with itself at the moment are centred around the premise that the relationship between record company as money-making-machine and musician as compliant-provider-of-noise-fodder should be maintained.

I, perhaps not surprisingly, think nothing could be further from the truth. So here’s my version of how record companies crapped on musicians even as they made countless millions for themselves:

The record label principle is basically that of a “spread bet“. In gambling terms, that means you split up the amount you have to gamble with across a number of bets, in the hope that the ones that win outnumber the ones that lose, and you come out ahead. It’s a system that worked for the labels, to remarkable success.

The problem was always in what they did with the ‘winnings’ – you see, if I’m putting money on horses or roulette, the only winners are me or the book maker. The ‘bet’ itself is neutral. The cards aren’t indebted to me if I lose. I’m gambling my money.

The record label model was that they were gambling our money on our careers, with precious little consultation, spreading the bets so they win, but still leaving the ‘losing hands’ in debt to them. Whenever Elton John had a hit, his label didn’t write off the debts of smaller bands. Instead, they pocketed the winnings and went straight back to telling the band that had lost on its first album what it needed to do for the second one.

On top of that, there are the mechanics of how the deals themselves were operated. The standard record deal worked out like this: a label lent an artist the money, to pay the label and its affiliates to make a record, charged them interest on the loan, and when it was paid off, still owned the product that the loan was for. They won 3 times!

When this was the only way to get a record out, we just had to grin and bear it. And to be fair, a heck of a lot of great music was made and released this way. (and, as you’ll see at the bottom of my fictitious graph, there were and are a lot of small labels that really care about music… they just aren’t, for the most part, particularly efficient…) However, an awful lot more music was squashed, lost or ‘stolen’, and a lot of great artists went bankrupt, leaving behind their future earnings to pay off the debts of reckless spending by the label that leant them the money in the first place.

But we had little choice. Print media was a monolith, radio a fortress, and while fanzines did their vital part in keeping sub- and counter-cultural arts alive, they weren’t a worldwide force to be reckoned with.

Clearly, now with all the resources we have available to us online, It doesn’t have to be this way.

- We can do it our way

- we can change the terms of the relationship

- we can opt out of “the industry” until such time as the industry does what it should’ve done all along – provide innovative ways to amplify the awareness of and message about great music.

Let the musicians make music while the non-playing infrastructure of the music biz just makes it easier to get that music out to as big an audience as is necessary for the artist to keep doing what they love. Audiences get better music, musicians get less interference from people who don’t understand what they’re doing and the industry side of things gets to focus on what they do best. Innovation and creativity win out in every way.

We are now in a position to consider the level of success that is optimum for our own happiness and as an incubator for our art. We no longer need to be constantly pushing to be bigger and bigger, selling more, being more radio friendly, making pointlessly expensive videos, doing grueling promo tours. No, we can define where we want to be and assemble the kind of help (if any) we need to get there, negotiating over what gets done and how much that is worth. We’re also then in a far better position to barter and swap skills with other musicians to reduce the needless costs of making music for all of us.

Take control. You can, it’s your music, your voice, your career. And don’t let any millionaire record company exec desperate to hold onto his greedy piece of the pie tell you otherwise.

Further Reading: This article from Wired Magazine about the Nine Inch Nails iPhone App, and all the other community-driven ideas they are implementing – outstanding innovation…

Comment ideas – what excites you most about the possibilities of a world where musicians make the music they REALLY want to make? Q2: how do we take the NIN ideas in the Wired article and apply them to an unknown or little known artist?