Have a listen to my new album while you read (it’s a long post):

2008-2012 was the tiny window in which the Internet looked like it really might be some kind of utopian amazing thing for independent artists trying to find a likeminded audience. With Twitter and Facebook in the ascendency, and neither of them messing with what you saw in your feed, there was a genuine meritocracy and an amazing space for indie artists to help spread the word about each other’s work without it impinging on their ability to reach their own audience. I put out a couple of records in that time, and they’re still my biggest selling digital albums. That’s no coincidence.

Then it all changed (in case you’re writing about this for college, the music economy can not reliably be divided into pre and post napster. The changes happened way more often than that, and as above, there were moments when it looked really good for us…) – Spotify came along. Initially without a mobile version or caching, it mostly replaced radio and a lot of people used it to find music to buy elsewhere! (some people still do, just fewer of them). But they pulled enough people into the streaming idea, and the prevailing industry wisdom was a really un-nuanced view that saw ‘legal streaming’ as the answer to torrenting stuff, rather than as a real and present challenge to buying stuff. Soon Spotify started ramping up the frequency of ads to make it really unpleasant without a paid account. (imagine being an advertiser who paid for an ad that purely existed to annoy people into getting rid of those ads? What a world…!)

And alongside that, first FB and then Twitter started to close off unfettered access to audiences. FB were blatant. On a given date, they introduced an algorithm that meant not everyone who was signed up to your artist page would see your stuff. Bands were literally having to cancel tours after having thrown their lot in with FB instead of a relatively costly email list, only to find that instead of 50K people a day reading their posts, it was less than a couple of hundred. Yup, it was that severe. No real warning, no room to manoeuvre, just ‘pay up, or no-one sees your tour dates’. And as most bands haven’t budgeted for that kind of contingency, there were tours booked on the assumption that 50K people would be engaged in knowing about and talking about them to help build an audience that crashed and burned.

Twitter was more subtle. First there was the shift of their ‘recommended’ users away from friends of the people that worked there that they thought were interesting (remember when brilliant and fascinating indie artists like Zoe Keating and Imogen Heap were on the recommended people to follow? The good old days…) Instead it was corporate accounts and reality TV stars. We were all being encouraged and subtly engineered away from forming meaningful open conversations with our friends and instead following celeb accounts, who in turn were paying for ‘promoted’ tweets, faked trending hashtags and the like. I still hold that the biggest enemies to conversation on Twitter are us all following way too many people, and the entirely bogus thought that our time is best spent trying to sum up how shit politics is in pithy Tweets that will salve the nagging feeling that we’re all going to burn. Seeing endless retweets and now seeing people’s faves in our timeline further ruins the experience…

And iTunes, once the supposed shining crown jewel of digital music shopping online (if you ignore all the BS with 128k files and DRM at the start), acquired Beats Music and morphed it into Apple Music. Their own streaming service, in direct competition to iTunes. They clearly give no shits about iTunes store, and would rather have the residual payments for people re-listening to old stuff than help current artists fund their work (TL:DR of streaming economics – it makes perfect sense IF 99% of the value in your body of work has already been released and sold in the past. If you’re a major label who also owns a publisher, then making money (and scraping metadata) from all the people who listen to The Beatles and Michael Jackson and Abba and The Eagles and the thousands of hit songs from yesteryear is WAY, WAY more profitable to you than those same people listening to vinyl or CDs that they bought in the last century. So you throw all new artists under the bus for that publishing money, and then pretend that the fight over higher royalty rates is one you even care about so the new artists don’t all leave. And if you can grandfather streaming into a record deal that still gives the label and publisher most of the money despite nothing being released, then you can make even more money and the artist gets basically nothing (see Peter Frampton’s viral complaints for evidence). Some indies are doing OK from streaming (if you keep all your rights and get some good promo elsewhere) but there’s no solid model for it as yet… In a nutshell)

But, through all of this, one only music entity kept growing, kept getting bigger, and better, adding music journalism, subscriptions, discovery… While Spotify was posting millions in annual losses and faking artists so they could stack their own playlists with shitty music that was published in-house dishonestly, Bandcamp grew and grew. $317 Million dollars to artists as I write this, and no losses. Also, no billionaire owners…

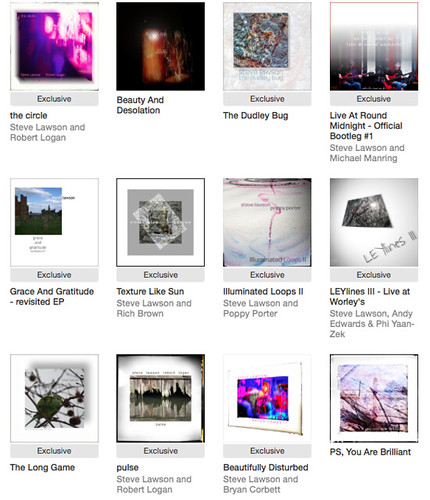

For me, as that fleeting utopian window faded, Bandcamp came up with the subscription idea. Offer people more music, more video, more interaction for an annual fee. The subscribers still get albums to download and keep (it’s still the bit of this that matters to me the most – nothing that anyone gets from me on Bandcamp is rented. It’s theirs. You aren’t paying for annual access to a thing that can be taken away. It’s yours (and in my case, it’s all Creative Commons licensed, so you can share it with your friends too – it makes no sense to me to criminalise people helping to spread the word). If Spotify goes down, all those curated playlists and all that data you’ve built up is gone for good. If Bandcamp goes down, all the music is yours (and equally valuably, my listeners are on my email list, so we don’t lose touch like we did on Myspace or MP3.com)

So what of releasing an individual album like I did yesterday? For me it has a number of functions. It’s good for me to stick a flag in the ground once a year – here’s what I’m up to, y’all – for those who aren’t already into what I’m doing, it’s a chance to explore it at album length. And for those who like some of what I do and not other bits, it’s a chance to buy an album at a sensible price and not have to subscribe to a bunch of music you don’t like just to get it!

YouTube for instrumentalists has developed a culture of wowing people with super clever tricks and monster technique. All fine except when it stops people from making any other kind of music. I’m acutely aware that my stuff on YouTube is never going to go viral. But I’ve also no plans to start making circus videos as adverts for something else. Great if your art leans in that direction already, but I’m more concerned about a diverse ecosystem for the arts, than forcing everyone into a particular mould to go viral.

Bandcamp doesn’t have that. I’m not trying to get a specific number of listens/views/clicks to make it meaningful. It is what they describe as ‘high friction’. It’s not designed for 20 seconds of wow before clicking out to somewhere else. The attention is on the art. And the invitation is to pay for it and help make more of it possible. If someone buys my new album, they aren’t paying off a budget for making or promoting it, they’re helping to make the next one possible. That’s why the monthly income from subscribers is so amazing. I worked out that I’d have needed somewhere north of 11 million Spotify plays to make what I’ve made on Bandcamp. That’s never going to happen making the music I make. I’d have to be thinking of ambient playlists as my target audience to try and make any money on Spotify at all. And that’s not what I do, it’s not what’s interesting about what I do, and it’s not why the people who subscribe to me are there.

My thinking on how music works online evolves a lot over time (dig back into my blog and you’ll see many posts where I was v much pro-Spotify at one point, and earlier than that where I had a really regressive and insane view of file sharing) but the knowledge that there’s no better environment for the sustainability of independent music online than Bandcamp has remained solid since 2009.

Thanks to everyone who made the defiant step of buying my new album. It would’ve taken me many, many thousands of Spotify plays to get the same level of income, and the ad campaign to get those plays would’ve eaten up all the money I made from it. Instead, a small group of people have made this record viable, by helping me to cover with download sales the money I’ve lost in the last week or so through illness-induced canceled teaching. That’s pretty amazing, and I’m grateful.

I’m not going to get rich, I’m not aiming to be famous, or to go viral. I just want to make more interesting art that reflects the world it exists in, and finds the people who care about that. Bandcamp is making that possible. Join the quiet revolution 🙂

An awful lot of music courses these days have group-based practical projects as at least one module within the course. This is, I think, a positive trend, in that it encourages you situate your learning within the context of your own practice as creative professionals, but it definitely requires some thought regarding how to organise yourselves in a group. So here are a few thoughts on how to do that:

An awful lot of music courses these days have group-based practical projects as at least one module within the course. This is, I think, a positive trend, in that it encourages you situate your learning within the context of your own practice as creative professionals, but it definitely requires some thought regarding how to organise yourselves in a group. So here are a few thoughts on how to do that: