“If only I had that pedal, I could do what I really want to”

“When I can afford a new mic, I’ll start recording some stuff”

“I can’t do what I want to do without Logic X, so I’m waiting til I can get it before I start my new project”

Musicians are so great at coming up with reasons for inactivity. And the vast majority of them are gear-related. We are so apt to mistake access to technology for skill and knowledge that there is a huge percentage of musicians at any one time sitting dormant, wanting for some tech solution. And meanwhile, so many of us don’t get on with the other half of that formulation – the skill and knowledge part.

Musicians are so great at coming up with reasons for inactivity. And the vast majority of them are gear-related. We are so apt to mistake access to technology for skill and knowledge that there is a huge percentage of musicians at any one time sitting dormant, wanting for some tech solution. And meanwhile, so many of us don’t get on with the other half of that formulation – the skill and knowledge part.

I recently taught a tech-related module in which almost every student went through some kind of period of inactivity due to a tech-related delay. Very few of them took a sideways step to explore the concept behind the thing that tech was meant to be allowing them to do, or came up with a more affordable version in the mean time. And inevitably, a lot of them ended up rushing towards the end of the year to get their projects done (caveat – the resulting performances were REALLY great, so this isn’t some kind of blunt ‘people who procrastinate will never achieve anything’ post 😉 )

The skills involved in music production can be practiced on the most rudimentary tech. learning how to position your phone to get the best audio recording via the built in mic will teach you a TON about acoustics and the directionality of mics. Positioning duvets and cushions and other stuff around it to soak up reflections will teach you about materials that are acoustically absorbent or not. Reaper is a DAW that’s available for super-cheap and on an extended trial basis if you’re super-broke (note: using Reaper perpetually without paying for it is a dick move. Don’t be that person) – it has virtual instruments, midi programming and the most incredible audio routing of any DAW I’ve ever come across. Taking audio recordings from your phone and learning how to improve them in Reaper will teach you more than waiting til you can afford Logic will ever do. (NB. I’ve used Reaper for all my recording, mixing and mastering for over a decade and can’t ever imagine going back to Logic or ProTools)

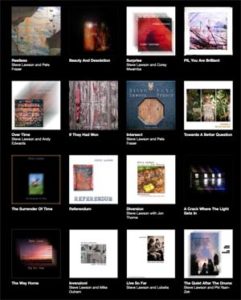

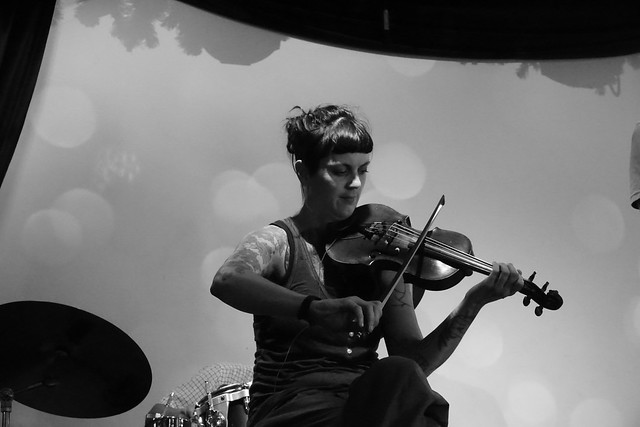

My current studio/live set-up (they’re the same) is the process of 26 YEARS of upgrades. In fact, I started 32 years ago with a borrowed distortion pedal, worked out what I could do with that, and moved on from there. My first album was recorded on Minidisc with an external mic – because THAT’S WHAT I HAD. I could’ve complained and waited til I could afford studio time, but the music wasn’t going to wait. I spent HOURS learning how best to position the mic, I sat with my friend Jez while he mastered it in the very first version of ProTools LE, getting him to explain everything he did so I could learn from that. My 2nd solo album was recorded into a trial version of Soundforge (hint – not designed as a recording program, at ALL!) via a Soundblaster gaming card. because THAT’S WHAT I HAD. My looping set-up changed over time, swapping things out, trading them in – I have multiple albums recorded with a broken (only worked in mono) DL4, and later on with a broken (produced intermittent weird digital glitches, and only worked in mono!) Looperlative, because THAT’S WHAT I HAD. I kept the same basses for decades because I didn’t expect new toys to fix problems that only practice could deal with.

My current studio/live set-up (they’re the same) is the process of 26 YEARS of upgrades. In fact, I started 32 years ago with a borrowed distortion pedal, worked out what I could do with that, and moved on from there. My first album was recorded on Minidisc with an external mic – because THAT’S WHAT I HAD. I could’ve complained and waited til I could afford studio time, but the music wasn’t going to wait. I spent HOURS learning how best to position the mic, I sat with my friend Jez while he mastered it in the very first version of ProTools LE, getting him to explain everything he did so I could learn from that. My 2nd solo album was recorded into a trial version of Soundforge (hint – not designed as a recording program, at ALL!) via a Soundblaster gaming card. because THAT’S WHAT I HAD. My looping set-up changed over time, swapping things out, trading them in – I have multiple albums recorded with a broken (only worked in mono) DL4, and later on with a broken (produced intermittent weird digital glitches, and only worked in mono!) Looperlative, because THAT’S WHAT I HAD. I kept the same basses for decades because I didn’t expect new toys to fix problems that only practice could deal with.

There’s a phrase that I picked up from photographer friends that’s used to shut down erroneous conversations about new tech – “The best camera for the job is the one that’s in your hands”

So for us, for today, we need to remember “What you have is enough, so what are you going to do with it?”

One of my music production heroes (and favourite music makers all round) is Andrew Howie, formerly known as Calamateur, who has made records with THE most basic tech you could possibly imagine. A lot of his gear has come from car boot sales and junk shops, or originally been designed as toys. And yet, he’s continually made extraordinary work. He turned whatever he had into the aesthetic of the project. I’ve been inspired by his records for nearly 20 years, and not once have I wished he’d had better tech (though he’s also now going through and remastering his ENTIRE body of work and reissuing them – go check it all out here, and subscribe! https://andrewhowie.bandcamp.com )

So, get good with what you’ve got – learn how to fix things, learn how to set up your instrument to get the absolute best out of it, find out what free software is out there (srsly, YouTube is THE GREATEST LEARNING RESOURCE IN HISTORY – watch tutorials in every spare minute you have when you’re not playing). If you’re making electronic music, sign up to pluginboutique.com emails and find out about amazing deals on stuff that’ll help you, and save up for the things you need. But while you’re saving WORK ON YOUR SKILLS. Your skills are not tech-dependent. Your dexterity using an MPC controller can be developed on the cheapest of USB interfaces, your understanding of mixing and mastering can be learned using built in plugins in Reaper, your harmonic and melodic ideas can be developed on a crappy instrument…

So, get good with what you’ve got – learn how to fix things, learn how to set up your instrument to get the absolute best out of it, find out what free software is out there (srsly, YouTube is THE GREATEST LEARNING RESOURCE IN HISTORY – watch tutorials in every spare minute you have when you’re not playing). If you’re making electronic music, sign up to pluginboutique.com emails and find out about amazing deals on stuff that’ll help you, and save up for the things you need. But while you’re saving WORK ON YOUR SKILLS. Your skills are not tech-dependent. Your dexterity using an MPC controller can be developed on the cheapest of USB interfaces, your understanding of mixing and mastering can be learned using built in plugins in Reaper, your harmonic and melodic ideas can be developed on a crappy instrument…

It’s OK to want and to save for great gear – at this point, I feel insanely blessed to get to make music with the tech that I have. But I didn’t wait til I had this to get to work. I used whatever I had and learned skills as I went along, upgrading when I could afford it, and working round it when I couldn’t.

Now, go practice.