So, last month my Bandcamp subscription reached a milestone – for the first time, the gross income from *just* the subscription was bigger than our annual rent on our house (which is also where Lo and I make music). That doesn’t include Bandcamp’s portion that gets taken off, but milestones are still fun to acknowledge and give us a sense of movement, progress and a way of benchmarking the journey towards creative sustainability.

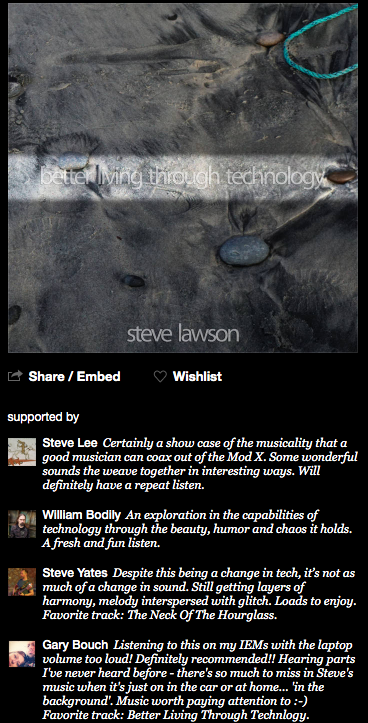

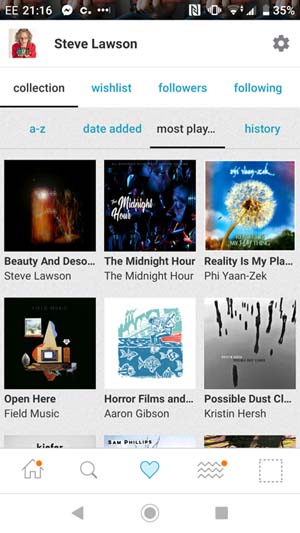

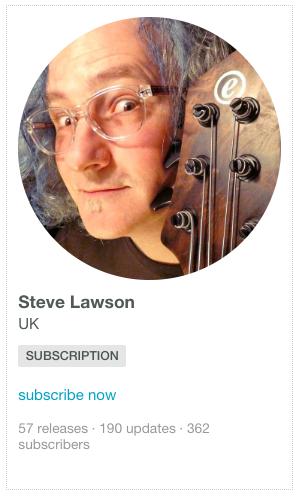

Then yesterday, I reached 250 subscribers. Or rather, 250 concurrent subscribers. Over the last 5 years, people have subscribed a total of 362 times, but some have let their subscription lapse (quite understandably feeling that they have enough Steve Lawson music by that point 😉 ) and others (a very pleasing percentage!) have let it lapse and then resubscribed later on when the new material looked too tempting to miss.

Then yesterday, I reached 250 subscribers. Or rather, 250 concurrent subscribers. Over the last 5 years, people have subscribed a total of 362 times, but some have let their subscription lapse (quite understandably feeling that they have enough Steve Lawson music by that point 😉 ) and others (a very pleasing percentage!) have let it lapse and then resubscribed later on when the new material looked too tempting to miss.

Now, what’s super interesting here is that the first stat – paying your rent with digital music – is the kind of statistic that’s often used to denote the viability of a musical enterprise… The most commonly used benchmark is ‘minimum wage’, but we’re always looking at real-world representations of music earnings. And in the age of streaming revenue, the point of those stats is generally to suggest just how far out of reach the size of audience required is for most artists. That to get US minimum wage solely from Spotify – according to a deeply flawed and probably out of date infographic from Information Is Beautiful – an unsigned artist (read: owns everything) would need 170,000 streams A MONTH. And that’s gross earnings, not net. There’s nothing in there factoring in the kind of ad-spend required to actually build that audience, or the way pursuing streaming audiences screws with touring economics, and how many other (properly paid) people we’d need to take with us on a tour that would help us build that audience… So my first stat about paying rent is one that plays well into the metrics of success that we’re wrestling with in the wild west of the digital music economy.

The second one, however, is ridiculous. 250 subscribers. an audience of 250 is tiny. A YouTube video that’s had 250 views doesn’t even register on our radar. A tour that had 250 people in the audience across it would be great if it was less than 5 dates, but as a gross figure for a longer tour, nah… 250 people isn’t a great deal…

So why is it that both numbers make me so happy? Let’s take a break to hear a tune:

This is the third track from my first album. Recorded live at the Troubadour in Earls’ Court in early 2000. My second-or-third gig there… The title is a reference to an idea explored in Benjamin Hoff’s book The Te Of Piglet – the follow up to the best-seller The Tao Of Pooh. The Virtue Of The Small is a pretty central Taoist notion, and invites us into a new (old) way of thinking about things. About specific things, but also about generalities. Valuing smallness runs counter to the economics of capitalism, and obviously to the attention economy of the digital music era. Smallness can be understood as advantageous in many ways, but for me in relation to the size of an audience, it’s about two things: community and expectation.

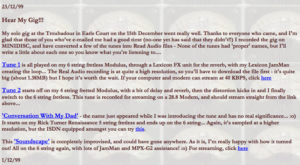

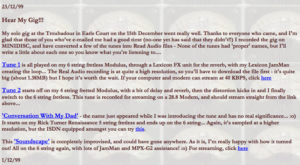

The community part is about managing relationships and being available to the people who are interested and invested in what I make and the how/what/where and why of it all. Realising that ‘the music’ as in, the recorded sounds, are only part of the experience was a pretty big moment. The build up to it started with my first album, and what was happening on this website before my blog – I had a news page (see image 🙂 ) that started out as gig dates, but soon started to feature commentary on what had already happened, trying to create a context, an expectation, and to explain what people were about to hear – both in order to help with the imagining of it all (this ‘everything live’ approach to music making was there right from the start, and all but one of the the tracks on the first album are single live takes – the last one was still single unedited takes, just one of them was an overdub – a fact I took great pains to explain…) but also to create an interest in it – back then, looping was a circus trick that had its own magic, so the explanation wasn’t just so people who were already listening would get what they were listening to – it was the ‘roll up, roll up, see the amazing looping bass guy!’ bit of the story. And in those nascent web-days, it played well. I had my fair share of angry email from dudes with Big Opinions about what you should and shouldn’t ever be allowed to do with a bass, but by and large it was a successful process.

The community part is about managing relationships and being available to the people who are interested and invested in what I make and the how/what/where and why of it all. Realising that ‘the music’ as in, the recorded sounds, are only part of the experience was a pretty big moment. The build up to it started with my first album, and what was happening on this website before my blog – I had a news page (see image 🙂 ) that started out as gig dates, but soon started to feature commentary on what had already happened, trying to create a context, an expectation, and to explain what people were about to hear – both in order to help with the imagining of it all (this ‘everything live’ approach to music making was there right from the start, and all but one of the the tracks on the first album are single live takes – the last one was still single unedited takes, just one of them was an overdub – a fact I took great pains to explain…) but also to create an interest in it – back then, looping was a circus trick that had its own magic, so the explanation wasn’t just so people who were already listening would get what they were listening to – it was the ‘roll up, roll up, see the amazing looping bass guy!’ bit of the story. And in those nascent web-days, it played well. I had my fair share of angry email from dudes with Big Opinions about what you should and shouldn’t ever be allowed to do with a bass, but by and large it was a successful process.

In 2002, I did a tour opening for Level 42 – some of you reading this blog will be here either wholly or in part because you found out about me around that time. If you want to connect with a massive global audience of bassists, opening for Level 42 is probably in the top 5 fastest ways to do that. But it also brought with it a bunch of quite unwelcome constraints. Opening for a big band like that made the rambling long-form improvisatory approach that has been my gigs up to that point untenable – you have to connect straight away or people wander off (interestingly, I heard Zoe Keating, who I knew back then through the Loopers’ Delight mailing list, tell exactly the same story about opening for Imogen Heap) – there was a need to be condensed, immediate, to grab people. And across that tour, I got pretty damn good at that! My between song chat became sharper (some of it was really terrible early on in the run, not really knowing that the kind of nonsense you can say in a venue to 20 people doesn’t connect at ALL in the Royal Albert Hall) and the tunes became way more focused… And the music lost almost everything that was fun about it.

In 2002, I did a tour opening for Level 42 – some of you reading this blog will be here either wholly or in part because you found out about me around that time. If you want to connect with a massive global audience of bassists, opening for Level 42 is probably in the top 5 fastest ways to do that. But it also brought with it a bunch of quite unwelcome constraints. Opening for a big band like that made the rambling long-form improvisatory approach that has been my gigs up to that point untenable – you have to connect straight away or people wander off (interestingly, I heard Zoe Keating, who I knew back then through the Loopers’ Delight mailing list, tell exactly the same story about opening for Imogen Heap) – there was a need to be condensed, immediate, to grab people. And across that tour, I got pretty damn good at that! My between song chat became sharper (some of it was really terrible early on in the run, not really knowing that the kind of nonsense you can say in a venue to 20 people doesn’t connect at ALL in the Royal Albert Hall) and the tunes became way more focused… And the music lost almost everything that was fun about it.

I remember finishing the tour, and a month or so later getting my first PRS (Performing Rights Society) cheque for playing my own music on those gigs – in the UK, whoever writes the music that’s being played gets a percentage of the ticket price, support act and headliner both. So while the tour itself did OK thanks to some really good CD sales nights (the small fee for each gig just about covered my travel and the amount I was required to pay the soundman for turning up a fader at the start and off at the end 😉 ) the PRS cheques were huge… I think over the next 18 months or so, I was paid about £11K for that one month of touring. So the temptation was to think ‘wow, two of these a year, and I can pretty much live on that and not have to scrabble around from month to month eking out a living!’

I remember finishing the tour, and a month or so later getting my first PRS (Performing Rights Society) cheque for playing my own music on those gigs – in the UK, whoever writes the music that’s being played gets a percentage of the ticket price, support act and headliner both. So while the tour itself did OK thanks to some really good CD sales nights (the small fee for each gig just about covered my travel and the amount I was required to pay the soundman for turning up a fader at the start and off at the end 😉 ) the PRS cheques were huge… I think over the next 18 months or so, I was paid about £11K for that one month of touring. So the temptation was to think ‘wow, two of these a year, and I can pretty much live on that and not have to scrabble around from month to month eking out a living!’

But, as I said, it pretty much ruined the music. It was so great to have the bigger audience, and there is a real buzz to having played those places. But the reality of being that far away from the people listening to me, and being that disconnected from any of the context (I, obviously, wasn’t booking the venues, wasn’t in any way involved in any of the organising, and only really got to hang with people by heading out to the merch table after my set – so the encounters all came with a commercial undercurrent) was a long way from everything that I really cared about as a performer. I’d got used to chatting to my audience, not shouting ‘Good Evening Bristol!’ at them.

My response was to spend the next few years trying to find the balance, and my records were a mixture of massive spacey improv and shorter melodic improvised pieces that I could re-learn and perform as a setlist. And that stuck for most of the next decade. That tension between wanting to just improvise – the records (except maybe Behind Every Word) being almost entirely improvised (I recently put out the first version of Grace And Gratitude as a subscriber release, which I didn’t have the tools to mix and master properly back then, so it was re-recorded) and playing tunes live because that expectation of a set list and the desire to sell CDs at the end of the gig of the tunes that people had just heard – that tension was present in all that I was doing then, but given that I was still recording everything live and allowing things to evolve in a live setting, it was all fine.

The turning point for me was touring with Daniel Berkman on the shows that became FingerPainting – our 10 album set of literally everything we’d ever played together. On those 10 shows, the only thing that didn’t get released was the solo tune that each of us did at each gig. We did them partly to give each other a break, and partly from that commercial thing of letting people know what else you do so they’ll buy stuff at the end of the gig. At the time my most recent album was 11 Reasons… and I played something from that at each gig.

The turning point for me was touring with Daniel Berkman on the shows that became FingerPainting – our 10 album set of literally everything we’d ever played together. On those 10 shows, the only thing that didn’t get released was the solo tune that each of us did at each gig. We did them partly to give each other a break, and partly from that commercial thing of letting people know what else you do so they’ll buy stuff at the end of the gig. At the time my most recent album was 11 Reasons… and I played something from that at each gig.

When I came to listen back to the gigs, with a view to mixing and mastering the music, it was startling just how consistently my solo tune was the creative low point of every gig. Daniel and I have a quite extraordinary chemistry – he’s one of my favourite musicians anywhere on the planet, and our taste and improvisatory impulses overlap in some near-telepathic ways. So that point when I go back to remembering a piece of music, and disengage from that flow-state of being in a place at a certain time with a specific group of people and making music FOR there and them, that was a moment of ‘meh’. I played the piece OK each time, it just wasn’t music FOR there. It was music to sell other music. And that’s a shitty reason to make music. I get why people do it – we don’t have the option of ‘escaping’ capitalism or its demands on us – but in the moment, it was so stark, that contrast between the spiritual/metaphysical experience of soundtracking an encounter and exploring all the things that had to go on between Daniel and I to make it possible, and that moment of ‘now I’ll see if I can sell some music with this nice tune’. Nope.

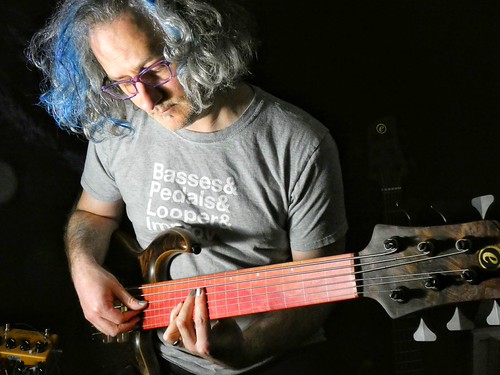

So I made a commitment at that point to go to all-improv shows. No more playing my own pre-written tunes. I’ll occasionally do a cover, if it’s something I don’t know too well and the improv impulse is still strong, but mostly, I’ll do whatever the space we’re in asks of me.

That coincided with the emergence of the Bandcamp subscription which became an affordance for a completely different way of thinking about the purpose and method of releasing music. I had had some input in the run-up to the Subscription service being launched – meeting every January with Ethan Diamond, Bandcamp’s founder, and making suggestions and requests (many that were taken on and others filed away for when they have time for my esoteric demands 😉 ). When they came to launch it, I was one of the three (I think) artists who got to trial it for a time before it was rolled out as an option.

And all of a sudden being an improvisor was a HUGE advantage. I wasn’t in the business of spending months in the studio writing, crafting, sculpting a set of songs that were then recorded with session musicians and engineers. I’d specifically spent the previous 15 years learning how to turn my studio and live set-ups into the same thing and learning how to mix and master my own music. I even did a course in mastering to be able to do it properly. The confluence of creative intention and platform affordance was properly amazing. I could record every show, and every show’s music was different. I could generate a huge amount in terms of value, and I now had a space in which to tell the story of why and how to an audience who weren’t being blocked from seeing it and engaging with it unless I paid for every message. (this was another thing I first did properly with the FingerPainting project, writing long sleevenotes to accompany the release that gave context to everything that was going on with it). There was no disconnect between access to the messaging and access to the music. It was all happening in the same place and the access mechanism was subscribing.

And all of a sudden being an improvisor was a HUGE advantage. I wasn’t in the business of spending months in the studio writing, crafting, sculpting a set of songs that were then recorded with session musicians and engineers. I’d specifically spent the previous 15 years learning how to turn my studio and live set-ups into the same thing and learning how to mix and master my own music. I even did a course in mastering to be able to do it properly. The confluence of creative intention and platform affordance was properly amazing. I could record every show, and every show’s music was different. I could generate a huge amount in terms of value, and I now had a space in which to tell the story of why and how to an audience who weren’t being blocked from seeing it and engaging with it unless I paid for every message. (this was another thing I first did properly with the FingerPainting project, writing long sleevenotes to accompany the release that gave context to everything that was going on with it). There was no disconnect between access to the messaging and access to the music. It was all happening in the same place and the access mechanism was subscribing.

So in setting the price of subscription and the minimum offer, I tried to find a place that made sense of what I was offering in relation to the value concept of ‘albums’ but also which allowed me to be really generous with my subscribers. I really didn’t want people to have to pay more just because I was on a roll. At the time, Patreon had a thing where people paid you for each thing you did – each track or YouTube video… That was so far from what I wanted. I wanted a fixed annual subscription, a minimum offering, and the opportunity to release anything that was worth releasing. I didn’t want to feel pressured to release stuff just to meet a quota, but I wanted to space to be prolific when my creative life afforded it. So the offering is, I think, two public and two exclusive albums a year, and last year I actually released 10 albums. Plus video, and a whole load of amazingly useful conversation with my subscribers. And because there are currently 250 of them, I can reply to everyone. I can handle them replying to things in multimodal ways. My last question to them about doing limited run CDs resulted in me getting replies on the subscriber thread, tweets, FB messages, email, email-via-Bandcamp, conversations in person at the Bass Show this weekend, and a mention in a phone call… We can work this all out as a community.

Which brings us to our second point – the first was community, we get to talk about the music, and there’s a palpable sense that each person is a meaningful and measurable influence on how I get to make music, and is part of an ecosystem that makes a very specific and non-standard kind of music possible. The second – closely related – point was expectation.

I recently visited the FB page of a friends’ band. They’re in a thrash band in the US, and were trailing their new album by posting videos from the studio. Almost every comment (over 90% of the comments) were expressed in the form of demands relating to the kind of music the poster wanted from the band… ‘yeah! It better be brutal!’ ‘hope you’re back to the heavier shit you used to do’ ‘man, that sounds great, hope it all sounds like that!’ ‘I’m not buying it unless it’s heavier than the last album – that was some lame shit’ etc…

Literally zero sense that the band are creative people making their music available, instead an incredible expression of fan entitlement to demand that the band conform to their expectations.

I occasionally get YouTube comments that drift into the same area. Back in the 00s I used to get a LOT of ‘you know what you should do…’ emails – ‘hey, Steve, do a record with a drummer!’ ‘dude, you need to do an all ambient record’ ‘hey, do a whole thing of tunes from films!’ ‘Why don’t you do a jazz standards album?’ – just nonsense that – being generous – came from a place of people enjoying what I did and wanting to engage with it, but mostly felt like people I didn’t know telling me how to do my job. I mean, those are LITERALLY the conversations you’d have with a record producer if you had one. Not the kind of thing that’s useful from some numbnuts on a bass forum.

So, how does this work out with the subscribers? You may think that given their level of investment in the music, they’d be pretty entitled about their role in it and make demands. But no, the nearest that gets is ‘oh I love it when you do music like that!’ – I do know which of my subscribers dig which of my modes of music making the most. I have one friend who’s been part of my solo music journey since the very beginning who *hates* samples of vinyl crackle. But has never said ‘don’t do that!’ because the expectation is that it’s all part of a community enterprise and the commitment on both sides is to making the art and the relationships around it possible. There’s no unit price on each album so if there are things on this album that someone doesn’t like, they’re not going to go ‘this wasn’t worth my money’, because the value is across a year, and includes the experience of making music possible, not just acquiring an artefact…

So, how does this work out with the subscribers? You may think that given their level of investment in the music, they’d be pretty entitled about their role in it and make demands. But no, the nearest that gets is ‘oh I love it when you do music like that!’ – I do know which of my subscribers dig which of my modes of music making the most. I have one friend who’s been part of my solo music journey since the very beginning who *hates* samples of vinyl crackle. But has never said ‘don’t do that!’ because the expectation is that it’s all part of a community enterprise and the commitment on both sides is to making the art and the relationships around it possible. There’s no unit price on each album so if there are things on this album that someone doesn’t like, they’re not going to go ‘this wasn’t worth my money’, because the value is across a year, and includes the experience of making music possible, not just acquiring an artefact…

Many, many of my subscribers are friends – a significant number are people I’ve met at gigs after they’ve become subscribers. Some have studied bass with me, some are colleagues, music makers, people whose music I love, even people who are on some of the albums. There are even journalists on there who’d have a better claim than anyone to actually requesting download codes for it all, but get that being a part of it matters.

The reasons for people jumping in and being a part of this are rich and varied, but that range makes for an incredible space in which to create – it gives me a degree of economic latitude not to have to think about how to market a particular thing (I even get super-lax about the public albums – I lined up basically no reviews of The Arctic Is Burning 😉 ) And I get to imagine the subscribers as an audience even when they aren’t present. Everything I record at home is video’d – the camera is the proxy for the subscribers. They get to see it if it comes out, and that’s their eyes as much as the laptop is their ears. I could livestream it, but they’d have to tolerate a lot of faffing between pieces 😉

So, sustainable economics out of micro-communities. I’m so incredibly grateful to get to do what I do, but so fearful that we’ll end up in a place where everyone expects to get ‘music’ from a streaming app and loses sight of the value of small-scale, low-stakes, community-based music making – the wider experience that Christopher Small named Musicking. The space to creatively explore within the bounds of a curious community instead of targeting a specific playlist, the space to tell little stories instead of grand gestures. The space to put out things that are interesting but broken because they have a story that makes them valuable, even if they’d fail on the radio or a recent releases playlist… I have some music on YouTube, but none of any of the commercial streaming platforms. It just doesn’t make any sense when my entire focus is this community. I really wouldn’t *want* 170,000 monthly listeners. I wouldn’t want the expectation they’d bring, the admin, the inevitable sense that they were supposed to be there and that I had to do things to keep them. Nope. I’m way happy with this life less ordinary 🙂

If you want to join the subscriber family, we’d love to have you. If you’re already in it, or have been at one time, thank you. Thank you from the bottom of my heart. All this music exists because you made it possible x

One last thing – December 15th is the TWENTIETH anniversary of my first ever solo gig at the Troubadour. So I’m doing a special anniversary show at Tower Of Song here in Birmingham. Stick it in the diary now, more details ASAP 🙂