TOO MUCH MUSIC?! What does too much music look like? Is it possible to have too much music? I know that there are some artists that have massive catalogues whose work I have no idea how to approach. Do you start at the beginning and work forwards? Do you jump in with the biggest selling, or just the most recent to see where they’ve got up to?

TOO MUCH MUSIC?! What does too much music look like? Is it possible to have too much music? I know that there are some artists that have massive catalogues whose work I have no idea how to approach. Do you start at the beginning and work forwards? Do you jump in with the biggest selling, or just the most recent to see where they’ve got up to?

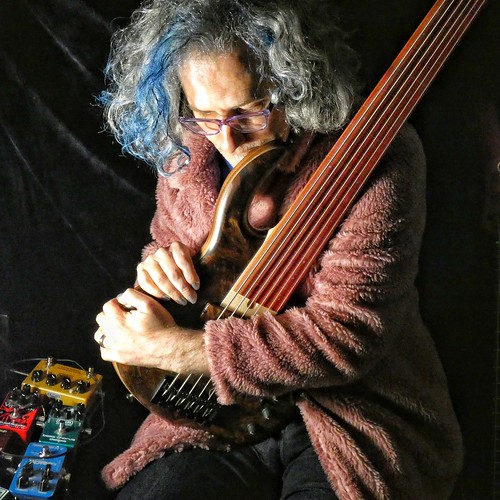

My own catalogue is, obviously, huge. I honestly don’t know off the top of my head how many albums I’ve released. That’s nuts, right?

So, anyway, to help you out, I’ve just gone over my solo output and annotated it a little as a Beginner’s Guide To SoloBassSteve – just a bit of context about each one. So of these albums are subscriber-only, so for those (and to get ALL of them right now) you’ll need to subscribe over at Bandcamp. The big thrill there is that once you subscribe, you OWN them all – it’s not a Spotify renting-access-to-streams-and-playlists thing, these are all yours. So if it takes you a few years to get through this lot, that’s OK. They aren’t going away. You’ll have them to download, stream via the Bandcamp app and even re-download if your computer dies as often as you like. The music is yours – click here to find out more about the subscription – http://stevelawson.bandcamp.com/subscribe

So, jump in, have a read, see how you get on, I’ll link to each album so you can just click through and have a listen!

2000 – And Nothing But The Bass – my first album, recorded live in concert except for the last two tracks, one of which was live at home, the other a duet with Jez Carr on piano. A bit like looking at baby photos for me now, but there are still quite a few people for whom it’s their favourite album of mine. Got ridiculously great reviews when it came out, probably reflective of how few solo bass albums there were then!

2000 – And Nothing But The Bass – my first album, recorded live in concert except for the last two tracks, one of which was live at home, the other a duet with Jez Carr on piano. A bit like looking at baby photos for me now, but there are still quite a few people for whom it’s their favourite album of mine. Got ridiculously great reviews when it came out, probably reflective of how few solo bass albums there were then!

2002 – Not Dancing For Chicken – first ever studio solo record. Was actually recorded twice, and I really wish I had all the earlier recordings still… Recorded direct to stereo two track, and destructively edited, still sounds pretty good considering. Features a couple of tunes that became live staples for the next decade – MMFSOG, Jimmy James and Highway 1. Was released while I w as on tour with Level 42, so solo VERY well on release, and got a fair bit of radio play, magazine coverage etc… remastered in 2012, to sound way better than the original, and also remove the comic sans from the artwork 😀 😀

2004 – Grace And Gratitude – probably still my most popular album – a consolidation of all the things I’d learned up to that point, and a pretty pivotal blend of all the elements that went into making up my sound at the time – big tunes, heavy ambient experimentation, beautiful chord progressions and weirdness! More radio support for this one, bizarrely. And I once reworked the title track for a beer advert, which sadly wasn’t ever used (mostly sad cos that meant I didn’t get paid… 😉 )

2006 – Behind Every Word – More composed that anything else I’d done to that point, features two amazing special guests – BJ Cole and Julie McKee, also was the first thing I’d released that had an outside co-producer (the 1st version of Not Dancing was co-produced by Jez Carr, but didn’t see the light of day because my insistence of recording with a mic’d amp was a stupid move) – this time it was Sue Edwards, who remotely monitored what I was up to, and gave pivotal feedback that made the album about 10 times better than it would’ve been…

2002/2004 – Lessons Learned From An Aged Feline Pts 1 & 2 – two very limited edition releases that came with the 1st 100 CDs of Not Dancing and Grace And Gratitude – lots of other things I was recording at the time. Started a trend for producing way more music than would fit onto a single CD…. (LLFAAF Pt 3 only exists as MP3s, and that came out with Behind Every Word) Pt 1 has my first couple of mahoosive ambient tunes on it, and they still sound good…

2010 – Ten Years On: Live In London – live album to mark the 10th anniversary of my first solo album. Recorded live at Round Midnight in London. Not a bad record of what I sounded like, but also the beginning of the nagging feeling that playing compositions wasn’t really what I should be doing live…

2011 – 11 Reasons Why 3 Is Greater Than Everything – first studio solo album since Behind Every Word, recorded in Catford and Muswell Hill. Remixed a year after it came out to reflect my improved skills as an engineer. Features a couple of my favourite ever solo tunes, and features LOTS of big tunes, and a little bit of epic strangeness – mostly reflective of how my sense of harmony had developed in the interim. Some less obvious tunes in there that I still really dig…

2011 – 11 Reasons Why 3 Is Greater Than Everything – first studio solo album since Behind Every Word, recorded in Catford and Muswell Hill. Remixed a year after it came out to reflect my improved skills as an engineer. Features a couple of my favourite ever solo tunes, and features LOTS of big tunes, and a little bit of epic strangeness – mostly reflective of how my sense of harmony had developed in the interim. Some less obvious tunes in there that I still really dig…

2012 – Believe In Peace – improvised live in an art gallery in Minneapolis, proved very popular, and still gets a lot of love today. I think this was my first all-fretless album… The artwork was from the amazing display of art by Geoff Bush that inspired the music. Recorded during a Tornado!

2014 – What The Mind Thinks, The Heart Transmits – the album that SO many people had been asking for for over a decade – a single ambient piece, recorded as the soundtrack to a guided meditation on a retreat. Super-popular with people who do yoga, meditate, or who just like really relaxing music to drive or sleep to! Followed another two year-long break from focussing on solo work following the life-consuming FingerPainting project!

2015 – Closing In (subscriber exclusive) – the first Bandcamp subscriber-only solo release, this was the ideas I’d started to develop on the journey to making the next two albums, and is the bridge between the first 15 years of my career playing only bass and nothing else, and then adding in the drums and synth stuff on the next two albums… ALL CHANGE!

2015 – The Way Home/ A Crack Where The Light Gets In – Two albums released on the same day, and the first things to come out publicly featuring my new set-up with the Quneo being used to play drums and some keyboard parts. Everything was (and is) still recorded live with no overdubs, but I have the option to play other sound and particularly to incorporate more obviously the hip hop influence that has been there in the background for my entire music life… Beats and weirdness galore – a new adventure to be sure!

2015 – The Way Home/ A Crack Where The Light Gets In – Two albums released on the same day, and the first things to come out publicly featuring my new set-up with the Quneo being used to play drums and some keyboard parts. Everything was (and is) still recorded live with no overdubs, but I have the option to play other sound and particularly to incorporate more obviously the hip hop influence that has been there in the background for my entire music life… Beats and weirdness galore – a new adventure to be sure!

2015 – You Guys, Let’s Just Talk About Nail Varnish – compilation of tracks recorded for the Bass The World YouTube channel.

2016 – Well, Say Hello Then (subscriber exclusive)Â – a lil’ EP recorded to introduce my brand new bass (my first new instrument in over a decade. Features some lovely ideas, is better than it’s slightly rushed existence might suggest!

2016 – Referendum – recorded just before and the day after the EU Referendum here in the UK. A hopeful then despairing collection of music that still emotionally resonates and became a favourite with a lot of people. Vertigo may be my single favourite ever solo piece…

2016 – Hands Music (subscriber exclusive)Â – Recorded at the launch exhibition for brilliant German photographer Marc Mennigmann’s ‘Hands’ photo project. Fully improvised as background/contextual music for the exhibition, is an interesting mix of very ambient and very poppy/tuneful. Has a couple of sneaky covers in there. V popular with subscribers…

2016 – Colony Collapse Disorder (subscriber exclusive)/ The Surrender Of Time / Towards A Better Question – 2016 produced a ridiculous amount of solo music from me… recorded in the same sessions, these three recordings consolidated the experiments that began with the previous two albums. The feeling of integration between the Quneo and the bass as a combined instrument, seeing the whole thing as one big music-generating thing, is way more fully expressed here (I’m even playing them at the same time on a couple of tracks) – Colony Collapse Disorder was originally just the first half, but a subscriber suggested that it felt like the beginning of something bigger, so I recorded the second half as an other track, put them together, and that’s what we have! The beat side of things is getting more varied and the hip hop more conspicuous.

2016 – Hark/Winter – Christmas single, that doesn’t really sound like a christmas single 🙂

2017 – Illuminated Loops (subscriber exclusive) – not really a solo album, even though it’s just me playing on it. The recording of my first performance with the great Poppy Porter – Poppy has synaesthia, which means she sees sound, so she draws what she sees while I play. I then treat it her art as a graphic score. It’s all kinds of fun and results in some very interesting music. My new favourite project.

2017 – PS, You Are Brilliant – a deep, experimental record with some big tunes but a lot of pretty intense textural experimentation, and deeply strange hip hop beats. A big step forward for the new set-up and probably my favourite thing I’ve released solo so far…

2017 – PS, You Are Brilliant – a deep, experimental record with some big tunes but a lot of pretty intense textural experimentation, and deeply strange hip hop beats. A big step forward for the new set-up and probably my favourite thing I’ve released solo so far…

2017 – Small Is Beautiful (subscriber exclusive) – the subscriber only accompaniment to the PS… only one track with any Quneo as all, lots of stuff with minimal looping and maximal mellowness. I love this, and is no doubt popular with all the subscribers who prefer my solo stuff from before I started messing around with electronics so much 😉

2018 – The Long Game (subscriber exclusive) – first solo release of 2018 is live album from the 2018 London Bass Guitar Show – both performances came out really well, and this is them. Foregrounding some of the Quneo-as-piano experiments I’ve been working with, rather successfully. Also the first solo release to feature my Elrick SLC signature fretless.

—-o0o—-

So there you go. I plan to do the same for the collaborations at some point soon. Hopefully it’ll help you dive in and find the ones you like the sound of! If you want to post your own thoughts on the albums, PLEASE do, either here in the comments, or via your Bandcamp collection so they appear next to the album!