Right, these thoughts come from a place of having had a subscription running on Bandcamp for over 5 years. I was one of the first three artists on there to get to trial it a full year before it went public. I was also consulted on what features it should have before they went live with it, so there’s a load of my thinking in there.

Right, these thoughts come from a place of having had a subscription running on Bandcamp for over 5 years. I was one of the first three artists on there to get to trial it a full year before it went public. I was also consulted on what features it should have before they went live with it, so there’s a load of my thinking in there.

I also subscribe to a whole bunch of people on Bandcamp – Thomas Truax, Corey Mwamba, Andrew Howie, No Treble and Julie Slick – and a range of stuff on Patreon – Divinity Roxx, James Chatfield, TheLitCritGuy, Double Down News and Jay Smooth.

I’m seeing a ton of people set up subscriptions and Patreons in the wake of the Death Of All Gigs thanks to COVID-19, and I thought it might be helpful to offer some advice. Take it or leave it, but at least give it some thought:

- Think about the value of what you have to offer. This may seem obvious, but it’s really easy to get caught up in what you think it’s worth to you to make it. But what you’re offering is a service. It may well be that people who sign up to it are doing so because they care about you and want to help maintain you through difficult times, but you’re doing that via the mechanism of a subscription to your art, not a begging bowl. So give a good thought to what you’re providing for the money.

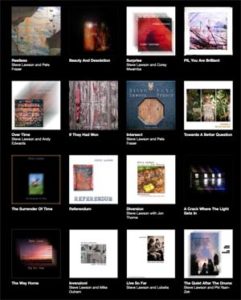

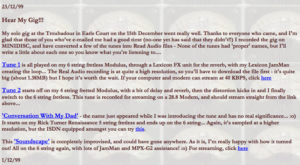

- This is a marathon not a sprint – be realistic about the work rate you can sustain when declaring what you’re going to do for people’s money, and don’t over-stretch yourself. I’ve seen so many people burn out by over-committing themselves to Kickstarter pledges, and it only gets worse if every month you’ve got to make a whole bunch of postcards or cakes or whatever and mail them out to people to keep your subscriber commitments. If you’re really into making stuff, that’s absolutely fine, and if the quality of what you make is consistent, and acquiring a lot of it is valuable that’s brilliant, but give some serious thought to what you promise. My own Bandcamp subscription promises 4 new albums a year – two public, and two exclusive. Last year my subscribers got 11 albums. The promise hasn’t changed. I love being able to over-deliver and not having to charge them more. It means people are way more likely to stick around, and you can have hilarious conversations with them about not being able to keep up. I’ve also included a couple of eBooks as extras, and as much video as I can produce that’s of high enough quality to deserve their time. All at no extra cost. The key concept is under-promise and over-deliver.

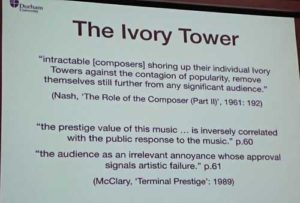

- Think about how what you’re asking impacts their ability to support other artists. I keep going on about this, but if you’re asking someone to spend the same on you as they would on their Netflix account, you’re leaving little room to support other artists. If any of the people I support in the list above were asking for £10 a month, I’d have had to decline. Because if they all did, I’d be broke. My subscription started at £20 a year, and has gradually increased until it’s now £30 a year. It’s still an absolutely ridiculous amount of stuff you get for that money – and the original subscribers are still on the £20 rate cos they get grandfathered in – and a lot of people have chosen to voluntarily pay more because they want to support what I do. That’s great, but I fully support them also being able to unsubscribe and resubscribe at the lower rate at any time so they can use that money to spend on other people. At the very least, it’s wise to have various tiers so there’s room for people who aren’t loaded to subscribe to you and not have to miss out on everyone else.

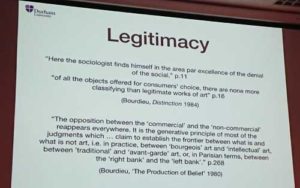

- Talk to your subscribers. This one is more about sharing some of the value I’ve got out of this. I’ve never had any interest in the idea of “fans†– I don’t want a bunch of fans who just get my music and dig it. I want a community of listeners who are actively engaged in the how and why of the music’s existence. So much so that I’m doing a PhD exploring what that means. (I’ve often described my grand project as being ‘how do I make music that matters without pretending I’m special?’) A subscription is an incredible opportunity to get to know the people who dig your music. Your subscribers aren’t a cash cow that pays your bills. They’re people who for whatever reason believe in what you do and the value proposition of the subscription offer. Do not disrespect that. Talk to them, find out about them, what they’d like, what else they’re into. Point them to other people’s work, build a wider community of people whose work your subscribers can share in.

- Think about the production values of what you can put out. Hearing crackly tape recordings of the Quarrymen rehearsing in the late 50s is amazing. Hearing your poorly thrown together demos for your next album is less compelling. Live bootlegs can be fun, but an endless supply of hissy recordings of the same tunes loses its interest pretty quick. If you’re an improvisor, or are constantly remixing and rejigging your material, or regularly learning cool covers, that’s tailor-made for a subscription model. Plenty of value, plenty of surprise. If you can collaborate, so much the better for adding variety to what you have to offer. If you’re going to do video, work on making it better and better over time. Running my subscription is an invitation to me to get better at every aspect of what I do – music, mastering, artwork, videos, story-telling… My subscribers aren’t a necessary nuisance that I’m putting up with for the money. They’re the most brilliant context within which to make work without having to come up with a marketing strategy for every album. If you’re not an improvisor, you need to work out how to tell the story of the one album you make a year in a way that is compelling enough to get people to pay for the privilege of being a part of it, or just charge way less so it’s basically an album pre-order thing that spreads out the money through the year. I’m surprised there aren’t more of those, to be honest…

- Don’t judge your own artistic merit by how prolific someone else seems to be. The way I make music, and the world I’ve built around me to make it possible is all 20+ years in the making. None of this is accidental. The actual terms of my Bandcamp subscription offering makes sense because I’m an improvisor who records every gig and collaborates as much as possible. I can make a LOT of music of a consistently really high quality and release it without any extra overhead. I did a mastering course to get better at it, I constantly practice the artwork side of it, I’m a journalist so the writing part of it is easier than it might other wise be. Your subscription doesn’t have to look like mine! If you want to have a really low stress, low impact one that just lets people support you in exchange for a new live track each month, it’s fine to charge 8 or 10 quid a year, and not pile on the expectation. Those people will hopefully stay with you, and as your offering increases, you can up the price. It’s also OK to make one album every so often and make the subscription about some other aspect of your work – lessons, or a studio documentary. Get the best camera you can, do it right, but telling stories is a brilliant use of a subscription. Beardyman has set one up that’s mostly about his process. You get his weekly songs, but also the chance to get deep inside how he does what he does. That’s a much higher value offering than most, because it’s lesson-based. Tuition has a different value metric to documentary work or finished art. People often have different budgets in mind for art-stuff and learning-stuff.

- Choose the right platform for what you want to do – Patreon and Bandcamp offer completely different sets of affordances for your art and storytelling. Bandcamp is, not surprisingly all about music. You can upload photos and video in the main message feed to your subscribers, but if you want to offer PDFs or any other file type, it either needs bundling with a single or album, or your need to host it elsewhere. On the other hand, Patreon is really rubbish at metadata on music files. And as far as I’m aware, still doesn’t do conversion to other files types for you. If you want it available as MP3, Flac, ALAC, AAC etc. You need to upload them all. The files can end up all over the place, with bogus formatting and variable quality. I couldn’t deal with that at all, so it would never work for me. That said, you can have a Patreon for storytelling, and just send your Patreon subscribers download codes for Bandcamp when the album comes out. Think about how the flow of media and information works and which offers the best platform. Neither is gofundme, neither is a begging bowl, both place you in an ecosystem where the people offering similar things around you become the standard against which your output and value will be measured to some degree. So think about it, and check out how easy it is to change the offering as you go along…

- My recommendation would be to start really cheap. Especially if you don’t have a ready made audience that have expressed a desire to support you like this. Get your initial backers in at the ground floor at a low monthly or yearly rate. These are the people who will be with you for the long haul, get them onboard ASAP for a low price and keep them close. You can increase it over time as the offering gets more polished and the value is reflected in the size of your audience. But don’t price yourself out of existence to start with. We have two main things against which we measure ‘value’ here – subscription costs to everything services (Spotify is $10 a month, Netflix a little more these days) and the cost of ‘albums’ – a similar amount for a single non-discounted album on iTunes or Amazon. Work out how to make your offering look like unmissable value. Then go to town telling people the how and why.

- Talk about it a lot. I’ve been on board with Bandcamp since almost day 1. I took all my music off almost every other platform 8 years ago because I was committed to what Bandcamp had to offer me in terms of the relationship with my listeners. I’ve been talking up its benefits for a decade, and the subscription specifically for 5 years. It never stops, you need to make a case for what you do. You need to make it compelling, and you need to do it over and over. For some of your audience, they’ve been told relentlessly that ‘no-one pays for music any more’ and that Spotify is how you ‘support music’. That’s clearly bollocks, but don’t look down on people who’ve bought into it. Spotify is horrible, and you may have to explain repeatedly why you’re not just putting all your music on there or the video on YouTube. Make the case firmly but gently.

- If you’re unsure how it works, subscribe to someone else for a while. There’s no better way to know what it’s like for the end user than to become one. Try some subscriptions out, support some other artists, see what you like and don’t like about what they do and how they do it. Research your project like you actually want to get it right!

Now, go do your research, and if you’ve got any questions, hit me up in the comments below.