First up, an acknowledgement that I haven’t written anything here for a year. That makes me a bad blogger. As well as this being the longest break in gigs since I was in my early teens (I literally played in more school orchestra gigs when I played violin than I’ve had actual shows in the last 18 months) it’s been one of not writing here either. For those that know, you’ll be all to familiar with the story of my ongoing PhD and how that’s taking all my writing time, but as I need to do some thinking about this topic right here, I may as well do it out loud. That said, this may be a very long post!

Sheila Chandra just shared this post to Facebook: “Jessamyn Stanley’s ‘Yoke’ Breaks Down Being Black In The Thin, White Yoga World” – I read it because I read pretty much anything Sheila shares. She’s a brilliant source of thought-provoking articles, news and commentary. And for whatever set of reasons, the FB algorithm actually lets me see a fair amount of what she posts…

There’s so much in the article that’s a vital read, so many areas in which people are marginalised and then looked at like they’re insane for raising it as an issue. Her story of being (in her words) a black, fat, queer woman in the world of yoga is as sad and enraging as it is depressingly predictable in the all-consuming fact of white supremacy and the extreme cultural appropriation of a millennia old Indian practice co-opted by rich, thin, white people. Read the whole thing…

However, the bit I want to address here is the quote in the extract from her book about social media, which though written about Yoga could just as easily have been written word for word about music. Here’s the extract:

“Teaching yoga on social media means fighting with your ego every day. Praying that it doesn’t eventually swell so large that you turn into a blimp. It means checking, constantly checking. It means posting, constantly posting. It means creating, constantly creating. But always with the other person in mind, always with your followership riding shotgun. The follower begins to color your inner sight. It becomes hard to see yourself without them. It’s hard to know yourself without them. It means constantly thinking of ways to do better, to do more than the other guy. It’s a never-ending state of comparison-no amount of work is ever enough and the idea of “good enough” becomes a fantastical myth. I don’t think it’s possible to work in social media without these feelings eventually rising to the surface. Frankly, I don’t think you can engage with social media at all without eventually arriving on this page.”

The horrendous contradiction between making ‘content’ to try and boost all those social media metrics that hopefully eventually lead to you getting paid (and may be part of the reason why you get gigs in this age of Numbers), and trying to put forward a presentation of self that speaks of your artistry, your integrity, your creative flair and passion… That absurd conflict between the need to self-promote and the idea that the stuff you’re promoting is free from the corrupting influence of the mess that is social media… The blandness of so much commentary on Facebook and Instagram, the obviousness of so much that happens politically, and the simple observation that the most radical of choices are the ones we don’t get to see, because the radicalism is in the choice to post things that don’t feed the algorithm, or even more so, to refuse to engage at all. The choice to be ignored rather than present an algorithmically-defined version of ourselves.

There is in this a second layer of corruption, that of our perception of audience. This is, I imagine where yoga and music might diverge. Perhaps not. There is some degree to which no matter how far we desire to de-commodify our practice as musicians, we’re ultimately making things that have a value, and we’re hoping to amplify that value, whether it’s the value of listening, the value of buying, the value of our audience branding themselves with merch and logos, the value of a concert ticket and the experience it represents as well as the value of talking about it afterwards, often resourced by us sharing the fumes of the experience and allowing them to circulate to extend the life of the show beyond its temporal constraints… We’re in the business of creating value, but we’re also in a far more complex relationship with our audience than that of supplier and consumer.

Stuart Hall wrote 40 years ago about the way that audience response feeds back into mass media, about audience reception being cyclical not linear (he broke it down into four stages: production, circulation, distribution/consumption and reproduction.) and it’s clear that audience reception and ‘use’ feeds back into our work, how we understand our work, how we relate what we do to our peers. Not just in terms of ‘success’ metrics but in terms of utility, the observable use that people find in our work. So that duality of ‘unfettered creation’ and ‘grasping desire for bigger social media numbers as a representation of audience and meaning’ is nonsense. The audience for our work is a vital part of the work itself, but perhaps we’re misunderstanding the degree to which they are actively present in the feedback which influences the kind of art we make.

In social media contexts, sharing is an act not just of re-distribution, but of alignment (sometimes in the inverse – sharing awful things to highlight our awareness of their awfulness…), and public reactions to things can hold multiple meanings and carry multiple layers of significance, depending on the context, the thing being commented on, the person commenting and our understanding of their relationship to us and the field we’re working in, our anticipation of how other people will interpret what they’ve said, even the use of specific emojis (yup, there’s a whole field of theory devoted to the semiotics of emojis, go look it up). And the thought that someone might share something without our knowing is.. well, unthinkable. Imagine somebody talking about me and me not being able to track it?? This is why so many of the native sharing tools have been added to networks, so we can generate more metrics with which to assume and interpret the meaning in those actions. Which in true Pavlovian style can lead us to replicate the successful patterns, a mode of engagement that leads inexorably towards a feed of selfies (smile and look into the camera, you’ll get more likes) and memes (who cares that they have literally nothing to do with your art, life, values or even sense of humour they get HUNDREDS OF LIKES!) The signal to noise of social media appears to worsen year on year as all the old memes stay in circulation (occasionally diminishing in fidelity as native shares become screengrabs in an attempt to remove a watermark and falsely imply originality…?) and new memes arrive.

But dealing with the fact that to hold onto your creative uniqueness might mean you have to be ‘bad’ at social media, to miss out on the stuff that gets other people views and likes, that leaves some of your posts languishing in ways that feel ignored despite the fact that they are connecting with exactly the people they need to reach in ways that are far more significant than a 1000 memes to try and game the algorithm – none of that undermines the rest of the ways in which your audience are absolutely vital to your work and your understanding of it. That audience may even arrive with you through social media, they may find you thanks to those same hateful algorithmic fuckeries that leave us feeling exploited or worse, ignored.

The mistake is to see social media as the end goal, to see the numbers as enough. Nowhere is this more apparent for musicians than YouTube and Spotify, the twin destinations for people craving viewer figures that are indistinguishable from phone numbers if you hope to make a living from the direct financial return. Both reward quite specific modes of creative work, both have led to changes in the modes of creative practice for musicians through the kind of actions they foster. In the case of YouTube, that’s been an explicit aim, to foster particular kinds of engagement in order to show people more and more ads, and to gather more and more data about those users. With Spotify, the consequential shifts in the way people make music seem to be largely be driven by hard economics (people need not to skip in the first 30 seconds for the track to get paid, so better not have a 63 second intro, eh?), as well as listening happening in a context where the next thing is always a click away. Add to that the promise of riches if you land on a genre or purpose-specific playlist (the sweet, sweet easy money of landing on a sleep playlist!) and you’ve got yourself a context in which the invitation to use ones creative skills to meet the needs of the market is there for all to see.

And, let’s be clear, that’s not a bad thing to do. There’s nothing remotely evil about musicians making music for a market. Music as professional craft is the same as any other skill at work in capitalism, whether it’s customer service or accounting. We can use musical training and the skills of cultural observation to make music for specific requirements. Music libraries the world over are full of work by people who excel at doing just that. Many of those tracks you hear at the end of hit use TV shows are written by people targeting those very slots, with publishers who know how to get the tracks to the right music supervisors. It’s a job, and it’s OK. As much as we’d like to be able to opt-out of capitalism, it’s a totalising system, so probably best not to hate on people for not starving, eh?

What’s weird about social media is that these B to B – business to business – transactions around music making get recast as B to C – business to consumer – mythologies, and music makers of all stripes get lost in the translation. And here the issues arise, when we have fewer distinct metrics of success, fewer ways of measuring meaning, we end up with a cultural hegemony of chasing social media numbers and specific forms of ‘success’ as monolithic within the creative industries. I’m amazed by the number of musicians who like the deer in Peter Rabbit just stare blankly into the headlights of the music economy and say ‘SPPOOOTTIFFYYYYY’, then set about doing what everyone else does on Social media to find an audience. Ignoring, of course, the massive, expensive marketing campaigns that are so often behind ‘viral’ successes…

While we’re on this, it’s important to remember that non of this is new, as David Hesmondhalgh has written, the streaming economy is worse than it could be, but not demonstrably worse than what came before. For many of us, what we miss isn’t the old industry but the VERY short period, from maybe 2007-2011/12 when social media felt way more meritocratic. It wasn’t, of course, in that it rewarded pushy, confident, shouty, funny people the same as any marketing context does. And there no version of reality where music by pushy people is demonstrably better or more worthy of attention than music by introverts, but during those years when we were inadvertently training the algorithms that Facebook and Twitter and Instagram would sell back to use from 2012 onwards, it felt like we were onto something new, something that really did cut through the stranglehold of the major labels on the attention economy in music.

But it was very shortlived. So we’re back where we were before the Internet, with those independents who manage to avoid the honeytrap of pursuing virality doing their best to make work sustainably, to keep making work they are happy to have represent them in the world. And hopefully to find an audience they can communicate with and listen to outside of the toxicity of social media environments, where the meaning and context and beauty and sheer usefulness of it all is absolutely in spite of the way its been built, not because of it. We’re resourceful animals and so much that is wonderful still happens on social media.

For me, I’d be genuinely lost without my audience. Actually, not lost, just different. I’d be distracted, I’d have a far less nuanced frame of reference for what the purpose is for all this tinkering with technology, for all the technique and harmony learning and practice. It could all just end up as 20 second Insta-videos, and endless stream of flyers with no gig, as Mike Watt might say. Maybe I’d end up spending time learning other people’s music rather than making my own, in the absence of any way to understand its value beyond these four walls. But the audience, my audience, specifically my Bandcamp subscription audience, are there as a reminder to make things, to land the plane, to tell the story of why this stuff exists, to give an account of why it wasn’t deleted, scrapped, rolled into a ball of bytes and recycled into something new. Why this? Why now? ‘Because people on Instagram like fast bass playing’ isn’t enough. it was never enough, it will never be enough. For me.

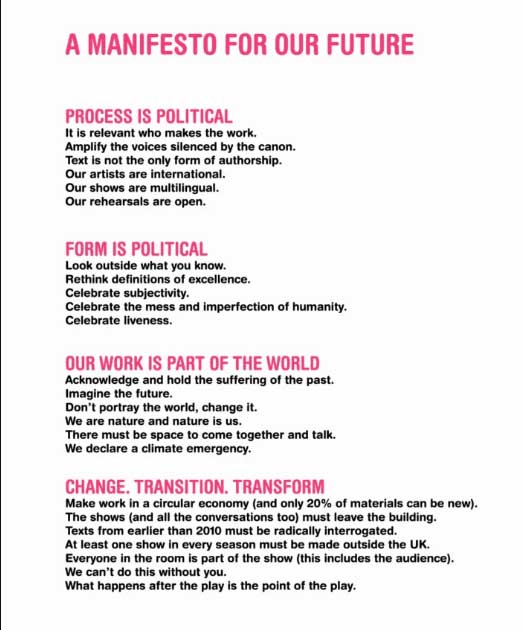

No mistake, that shit is as beguiling as it is toxic, and it’s the environment we occupy. Whenever there is a crossover in what I make and what distracted bass-owners want to see on Instagram (usually because ScottsBassLessons share it 🙂 ) I wonder if I should do more of that, if Pavlov’s chops should be flexed to gather more into the fold. But I know that it’s an over-served field. There are enough videos for people who like that stuff, whether they know it or not. It’s a space that distracts, that stops me from doing what I care about, and stops me from connecting with that audience who give meaning and context to the work, who tell me what it means to them, how they use it, who invite me to Do My Thing. One of the ways I try to keep my head clear is to have mini-manifestos for what I’m trying to do. They’re more for me than anyone else, but making them public helps with accountability – “trying to make music that’s important without pretending I’m special”, “making the music that I think should be in the world but isn’t” – that sort of thing. Even the strapline from my website started out here – “the soundtrack to the day you wish you’d had” – an invitation to myself to make music imbued with hope.

If you make work that is for anyone but you (I’m suspicious of anyone who says they make music just for themselves, purely because if I know they make music, then they’ve chosen to at least talk about it elsewhere…) you may find yourself in need of some time to consider who it is for and how to find them. The economics of social media push ever further towards an understanding of audiences as a massive crowd of faceless avatars, who need understanding through metadata and ad revenue matrices, who can be reached through shared interests and the pages they’ve liked on Facebook. But if your tribe is small, or strange, or disparate, or heterogeneous, or you just want to say HI to them, you’ll need to look elsewhere, to do the work to swim upstream, to divert energy and attention away from the social media waterfall.

Keep your head, and if you need to talk it over, find likeminded friends to hold you to account and push you to find your soul in the midst of all the metrics. And come find me on Bandcamp.