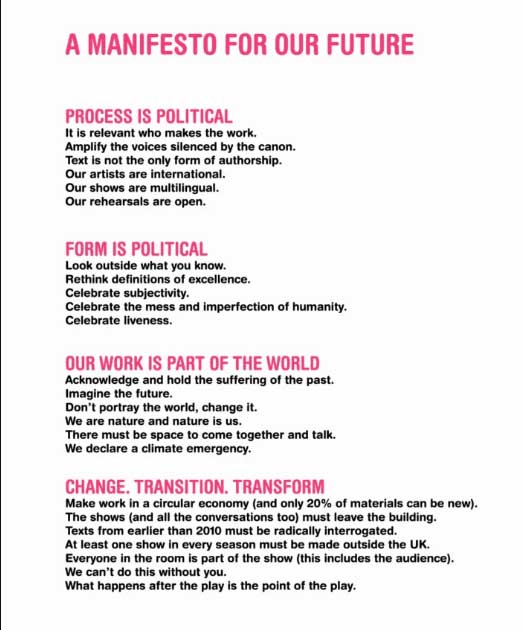

Yesterday, I came across a gorgeous thing on Twitter. It’s the manifesto of Gate Theatre in Notting Hill:

It’s a beautiful mix of ideals, ethics and concrete commitments. It lays out what they want to do, how they want to do it and the moral standards that are to be held to while they do it. And none of it commits to making a particular amount of money for shareholders, or to meet funding requirements, or to getting a certain amount of reviews or any other typical metric of success. It’s not that none of those things will happen or are even necessary, it’s just that with the manifesto in place, the mechanisms for making them happen are now subservient to the operational code laid down in the manifesto. They are now people of The Way. They have a document to refer back to whenever they make decisions. (I have a deep love for Gate Theatre anyway, as it’s the first place we ever did Torycore 🙂 )

And it made me think about how little of what we do in music is based on any kind of meaningful thought-out foundational principles. I mean, EVERYONE has things they are working towards, but most of them are based on the received wisdom of ‘the industry’ (spoiler alert: there is no ‘the industry’) – and way too many artists let go of what they assumed were their artistic goals in order to meet a set of commercial ones imposed from outside. Again, if that’s your aim, cool, write it down, commit to it and do it honestly. But for a huge number of musicians, there’s a massive disconnect between what they think they’re trying to do, and what the mechanisms they are pursuing are for, or what they almost always bring about.

Let me tell you about two manifestos I’ve been involved with. The first is an easy one – when I was a part of New Music Strategies with Andrew Dubber, we first convened in The Netherlands in January 2010 to decide what we wanted to do. There were five of us, and we stuck post its all over a wall and talked a lot about what we thought we had to offer. But at the heart of it was a very simple manifesto that we agreed on – “to help bring more music to more people in more places”.

It gave us a focus that was about what was good for music in its widest sense, rather than getting distracted by individual quests for ‘success‘ or a particular sector of the global music economy’s obsession with the numbers in their spreadsheet. It helped us decide what we did and didn’t want to do, and led to us turning down a very well paid offer to shepherd the career of a teenage starlet whose overbearing uncle (I think) was utterly convinced that we were the ones to help her become a star. Our response? Go to college, do things you love, make the music you care about and stop worrying about being famous. Not something anyone was going to pay money for. But we ended up doing all kinds of good stuff with NMS during the period in which it was a 5 person team. And none of it compromised that central manifesto.

The second one has only ever been seen (before now) but a couple of people – it was borne out of a joke project with a friend, but contains so much ridiculous truth about how I think about music that I really need to cannibalise it for a manifesto of my own. The project in question is an imaginary band called The Steveness, with my friend Stephen Mason (out off of Grammy-winning, multi-million rekkid selling pop stars Jars Of Clay) – the unique situation in which the Steveness find ourselves is that we’re so good we can’t actually make any music or everyone else will just give up. We’ve never played a note, out of kindness to the rest of the planet. So back in 2015, no doubt after spending a little too long on Bill Drummond’s website, I decided that The Steveness should exist as a Manifesto, and so I wrote this, and sent it to Steve for his birthday:

A Steveness Manifesto

Music Is Not A Product

Music Cannot Be Bought, Sold, Taken, Manufactured or Contained.

Music Is An Experience.

Music Is The Context For Experiencing The Experience.

Music Exists Only In Time as Expectation, Experience And Memory.

Music That Is Sometimes Never Was.

Music That Will Be May Not Be.

The Home Of Music Is The Memory.

The Chorus Remembers The Verse. The Bridge Remembers The Chorus

You Do Not Hold Music. It Holds You.

You Do Not Own Music. It Owns You.

Music Is Fleeting And Eternal.

Music Is Made Possible By Ideas, Aided By Performance, Shared By Recording.

Music Is A Conversation.

A Conversation About Music Is Music.

The Steveness Is Music.

The Steveness Is

The Story Of Music

An Encounter With Music

The Idea Of Music

The Soul Of Music

The Steveness Is Dangerous, Beautiful And It Exists In Your Memory.

The Steveness Is A Memory Of A Reality That Never Was And May Never Be.

The Steveness Is

A Memory.

The Knowledge Of Greatness.

An Experience Beyond The Senses.

The Steveness Is.

-o0o-

Now, the bizarre thing about this is that the first half of it, before I invoke the name of the Steveness, is all about music as a phenomenological proposition, written a year or so before I’d heard the term phenomenology. It also encapsulates some of what Christopher Small’s seminal work Musicking is about. Even though it was me using the frame of ‘other Steve and me mucking about’ as a way to think about the true ephemerality of music. It’s ended up as a reimagining of John Cage’s 4’33” for the Flight Of The Conchords generation.

So, my suggestion for you is, go and write your manifesto. What matters to you? What’s truly important in your life, your work, your art? Write it down, print it out, refer to it when you make decisions. Cos without it, if you’re in music, you’re going to end up doing a lot of shitty gigs and being put under a whole lot of pressure to change what you do to fit someone else’s idea of sellable.