Today is Joni Mitchell’s birthday. She’s 68.

Joni has influenced my music perhaps more than any other single musician. She’s not a bassist and she doesn’t loop, but the connection her music makes, the way it draws you into the story, into her world, the feeling of almost too much access into the inner recesses of her mind, all wrapped in just the right music for each story, is exactly what I’ve tried to do. Her music is the gold standard. Continue reading “10,000 Jonis – Celebrate by Sharing.”

London gig on Aug 25th – the Singers Of Twitter :)

This is the first proper London show in AGES for Lobelia and I, so we’re making it a special one. We’ve asked 3 of our favourite singers to join us for an amazing night of singer-songwriter-ness… and genius Ukulele magic. It’ll be on Aug 25th, doors at 7pm, music from 7.30, at Darbucka World Music Bar, on St John’s Street in Clerkenwell, London. Continue reading “London gig on Aug 25th – the Singers Of Twitter :)”

This is the first proper London show in AGES for Lobelia and I, so we’re making it a special one. We’ve asked 3 of our favourite singers to join us for an amazing night of singer-songwriter-ness… and genius Ukulele magic. It’ll be on Aug 25th, doors at 7pm, music from 7.30, at Darbucka World Music Bar, on St John’s Street in Clerkenwell, London. Continue reading “London gig on Aug 25th – the Singers Of Twitter :)”

Jonatha Brooke playing the UK this week.

Quick post before a proper blog update later on.

Quick post before a proper blog update later on.

One of my favouritest singer/songwriters in the whole world is playing in London this week. If you’ve been reading this blog for more than a few months, you’ll have heard me go on about Jonatha Brooke before. She’s an outstanding singer, songwriter, guitarist, story-teller, performer. All round marvellous. And she’s in the UK at the moment:

Tues 24th – Leicester, The Musician

Wednesday 25th – Norwich, Arts Centre

Friday 27h – London, Bush Hall

Sun 1st – Salford, Lowry Centre.

Really, you shouldn’t miss her. Lobelia and I will be at the London gig on Friday, so come and say hi. Here’s a Youtube vid to whet your appetite – there’s plenty more of her on there, or on her website at jonathabrooke.com

Interview with singer/songwriter Martyn Joseph…

Another lil’ interview, that brings together so many of my interests 🙂 Martyn’s an amazing singer/songwriter, and has been running his own label for over a decade. He’s recently been opening for Ani DiFranco in the States, and has been through so many different parts to his career, from churchy-singer-dude in the 80s, to Sony-signed almost-pop-star, to political, social poetic acoustic troubadour. Here’s a really lovely interview with Martyn about all of those things 🙂

The Musical Mechanics of 'Feeling': Wordless Story Telling

Right, here’s a blog post I promised on Twitter at the beginning of the week, but have only just got round to writing. Here were my original ‘tweets’ –

solobasssteve “Blog post idea – the musical mechanics of ‘feeling’: ambiguity, journey, wordless story-telling and narrative/soundtrack quality…”

solobasssteve “Gifted singers routinely sing like they’re still discovering the unfolding tale of the song. Instrumentalists rarely play like that…”

One of the things I work most hard on in my music is developing the relationship between phrasing and feeling. Learning how to play a tune as though it has words and is telling a story. For that reason, most of my biggest influences are singers; the musicians I try and emulate are those whose music strikes me on an emotional, feeling level rather than a technical, heady one.

I often find myself left cold by instrumental music that on the surface I’m impressed by, but which doesn’t seem to soundtrack any part of my life, does reflect anything about the way I think or see the world. And I think I know why…

The big problem with most of what gets lumped together as ‘fusion’ or ‘electric jazz’ is that the way the music is played makes it sound like the artist has all the answers. Like there’s no search, no journey, just an arrival point. And that arrival point is one of dexterity and chops, with the compositions often stemming from a similar place. Or even with the compositions actually being pretty deep, but still being played from a position of having it all sown up before the tune starts.

Great singers never do that. They tell stories, the adopt characters, they emote according to the narrative. They often sing like they are discovering for the first time the unfolding tale of the song. It’s way more important to communicate than it is to show of their wikkid skillz. Having a big range in your voice is part of the singers emotional palette, and is rarely used for shredding (Maria/Celine etc. aside…)

So it’s no coincidence that my favourite instrumentalists also play like that. Bill Frisell is a fantastic case in point – a phenomenally gifted guitar player, who has leant his wide ranging guitar skills to a whole load of different projects, but who always digs deep emotionally. He plays guitar like a world-weary country singer, or a heart-broken torch singer. He does the full range of emotions, rather than sticking with the slightly smug, self-satisfied gymnastic displays of many instrumentalists.

Nels Cline is the same – he can be sad, angry, playful, child-like, inquisitive, tearful, tender… all in the same solo.

And of course there’s John Coltrane, the Godfather of story telling improvisors, unfolding the story of his spiritual quest on the stage each night via his sax. Phenomenal technical skill, completely at the service of the music, or the story, and always stretching, searching, telling stories as they occured to him, risking the blind allies, crying and screaming through his music when it was required.

Q – “So how do I as a bassist head in that direction? What are the mechanics of feeling? How do I move away from dextrous but lifeless technical cleverness and start telling stories?”

The start point is listening and a little analysis. Take a singer you love, a singer that moves you, a singer that connects – what are they ACTUALLY doing? What’s happening in terms of dynamics and phrasing? Where do the notes sit on the beat? Take 16 bars that you really like and learn them. Start by singing them, then play what you sing. Not just the notes, but the dynamics, phrasing, articulation. The whole works. As close as you can get. How far is that from how you usually play?

Here are a few musical elements that aid us in sounding a little more ambiguous, discursive, narrative:

- stop playing everything on the beat: Bassists are the worst for this, but a lot of jazzers too – we end up drawing a metric grid in our minds and stick to it. Divide the bar into 8/16/32 and play those subdivisions. Go and have a listen to Joni Mitchell and tell me how often she’s on the beat. How often her phrasing is metric. Pretty much never.

- Start using dynamics: I’m amazed at how few melody players in jazz – particularly guitarists and bassists – rarely vary the dynamics of what they do.Have a listen to this Bartok solo sonata for violin – hear what’s being done with the phrasing and dynamics? It’s incredible.

Alternatively, have a listen to Sinatra, to the way he pulled the melodies around, and used his amazing control of dynamics. Remarkable stuff. In the rock world, check out Doug Pinnick’s vocals with King’s X. He’s closer to singing in time, but exploits the variation in being ahead of or behind the beat beautifully to spell out the emotion of a song.

- Vary your technique – again, very few singers sing in one ‘tone’ through everything. Those that do usually get tiresome pretty quick. Most of them use tonal variety the way we do when we talk. Getting louder will vary the tone automatically. Same with your instrument. The number of bassists who play with their thumb planted on top of the pickup, using their first two fingers in strict alternation even for playing tunes is bizarre. Bassmonkeys, Your right hand is your primary tone control – forget EQing, and work with the source, where the subtle variations are from note to note. moment to moment, phrase to phrase. Experiment, keeping in mind what you’re trying to do – tell a story!

- Play less notes – At NAMM every year, I get other bassists – often pretty famous ones – coming up and asking me how I play so ‘soulfully’, or so ‘deeply’ or whatever. Admittedly, their reaction to what I do is going to be exaggerated by the lunacy of all the shredding going on, but the simplest answer is often that I play less notes than most of what they are used to listenin to. Again, it’s a singer-thing. Very few of my favourite vocal melodies are technically hard to play. Some have some pretty big intervals in them (Jonatha Brooke, one of my favourite singer/songwriters on the planet, writes some of the most amazing melodies, and has an incredible way of delivering them. She uses really unusual intervals but never sounds like the cleverness of the tune is getting in the way of what’s being said…) So just learn some vocal tunes. Actually, not just ‘some’, learn loads! Get deep into what singers do. Take songs and listen closely to how the tune develops from one verse to the next. Again, great story tellers adapt the phrasing to the emotion of the story, they don’t feel the need to add more and more notes as it goes on…

- Play simply… even the super fast stuff! – the genius of Coltrane was that he very rarely sounded like he was struggling with his sax. He was wrestling with music, and emotion through his sax, he was digging deep to find the soundtrack to his inner journey, but his horn was at the service of that journey, not directing it in a ‘check out this clever shit’ way. Dexterity is a wonderful thing. There’s nothing at all wrong with being able to sing or play really fast. It’s just that it’s not an end in and of itself. Some things sound fantastic when you play them really fast. There are tracks by Michael Manring and Matthew Garrison that have an incredible energy rush to them because of the pace. They wouldn’t have that if they were slower. But neither player sounds like the tunes are a vehicle for a load of mindless shredding. Im always looking to improve my technique by deepening it. Speed is definitely part of that. But it’s just one aspect of control. And control is the key.

I find it really odd when I hear musicians that site Miles Davis as a big influence and then proceed to play like the entire story of the tune was set in stone years ago. Like there’s nothing to add, nowhere new to go, no need to dig deep. Miles is the Yin to Coltrane’s Yang. Miles was a pretty good be-bop trumpeter in the late 40s/early 50s, but he didn’t really have the chops of Dizzie or Chet Baker. And yet he had a quality to his playing, even on crazy-fast bebop stuff, that drew you in, that took you with him… That got deeper and deeper as his life went on. With a cracked and broken sound, he told stories, and wrung out old melodies to find new tales. He also never went backwards, constantly searching for new things in music. The narrative of each solo was reflected in the meta-narrative of the arc of his career. No resting on laurels, lots of progressive work, and not a few false starts along the way. But he was integral to just about every new thing that happened in jazz from the early 50s onwards.

We need to dig deep to find this stuff. It’s not something you just do. Its not something easy, it’s not a lick you can learn and regurgitate, or a solo by such and such a player that you can transcribe. It’s a desire and a search and a longing to tell stories that comes out in our playing, that shapes the way we practice, the kind of musicians we choose to work with, and the risks we take. If you want some inspiration, try looking up some of the following on last.fm:

Guitarists: Bill Frisell, Nels Cline, David Torn, Mark Ribot

Bassists: Michael Manring, Matthew Garrison, Gary Peacock, Charlie Haden

Pianists: Keith Jarrett, Herbie Hancock, Jez Carr, Alan Pasqua

Singer/songwriters: Joni Mitchell, Tom Waits, Paul Simon, Gillian Welch, Jonatha Brooke, Lobelia, David Sylvian, Kelly Joe Phelps, Robert Smith (The Cure), Frank Black (The Pixies)

Music is about way more than impressing other musicians. There’s nothing wrong with musicians being impressed by what you do, any more than there’s anything wrong with people thinking you’ve got a cute accent when you talk… but what you say is what will sustain the value in the long run… Dig deep.

Bruce Cockburn interview from Nov '99

Back when I was writing for Bassist magazine in the late 90s, I mainly used interviews as a chance to meet up with my musical heroes. The bass ones were easy to sort out, but on a couple of occasions I used the magazine connection to interview my guitar playing heroes as well, and did this interview for Guitarist magazine. Given that Bruce Cockburn is my favourite musician of all time, and probably the songwriter whose songs have had the most real-world impact on my day to day life, it was always going to be a little hagiographic, but I think I’ve kept the ‘you’re amazing, tell me about being amazing’ type questions to a minimum.

This is my original transcript of the interview, which is a fair bit longer than what actually got printed, I seem to remember. It was just after Breakfast In New Orleans, Dinner In Timbuktu had come out, and was conducted in the restaurant of some hotel in Ealing, I think. Bruce was a fantastic interviewee, and this is one of my favourite interviews to read back. A couple of my questions are a little crassly put, but it was 9 years ago, so I’ll cut myself some slack. I’ve met him a few times since, and he’s always been a very friendly, funny person to meet…

Bruce Cockburn Interview

(Reproduced from the November 99 issue of Guitarist Magazine)

Impossible to pigeon-hole, but equally brilliant whether finger-picking ragtime instrumentals or giving it what-for on a distorted electric, Bruce Cockburn’s artistry continues to climb 30 years into his career.

Once described by Melody Maker as ‘Canada’s best kept secret’, singer/songwriter Bruce Cockburn has, over the course of 25 albums, built up a substantial following world-wide and is a bit of a superstar in his native Canada. He’s had 20 gold and platinum records, won 10 Junos (the Canadian version of Grammies), and does seriously big tours, but remains a cult act in the UK (albeit a cult act capable of playing the Queen Elizabeth Hall on London’s South Bank last time he visited these shores!)

Bruce’s body of work ranges from lilting country folk to the dark brooding punk and reggae influenced political ranting of his eighties albums. His recent move to the Rykodisc label has been accompanied by a shift back to the jazzier acoustic sound of his late seventies albums. Always focused, Bruce is one of very few singer/songwriters to last 30 years with no embarrassing period whatsoever.

Initially inspired by Scotty Moore and Buddy Holly, followed soon after by Chet Atkins and Les Paul, his guitar playing encompasses a huge range of styles, taking in ragtime and blues influences but combining them with jazz, country, rock and avant-garde in a unique melange that perfectly supports his heart-felt prose.

– When did you start playing

I started playing when I was 14 which was 1959.

– Why?

Scott Moore – the early Elvis records. Buddy Holly… well, the sound of the Crickets – I didn’t really associate it with particular people it was just music. That’s what got me excited about music. I started taking guitar lessons at the age of 14 and was very quickly introduced to other kinds of music. The teacher I had was into country swing like Les Paul and Chet Atkins, and all the tunes that were on Willy Nelson’s ‘Stardust’ album were the tunes that I learned to read music on the guitar with, to learn chords and all that stuff. The first tune I can remember actually working out off a record was ‘Walk Don’t Run’ by the Ventures. It just kinda moved on from there – I got interested in jazz pretty quickly, and through that moved into folk-blues. By the time I got out of high school I was doing some rudimentary finger-picking and was starting to compose music, and dabbled in writing poetry. I went to Berkley for three semesters out of a four year course, and did what all honourable Berkley students that are any good do – drop out! Last year they gave me an honorary Doctorate so I finally got my degree. When I was at Berkley I was shown by John Lennon and Bob Dylan that you could actually put poetry and music together and make something.

– So Dylan was the catalyst?

That’s what interested me about it. I had no interest in imitating the songs I liked – old Elvis songs, ragtime tunes – those were the product of a time and place and an experience that I had no part of so it made no sense to try and write those songs. It was OK for me to sing them, that made sense, but not trying to write anything like it. But it hadn’t occurred to me that you could do anything else until Dylan came along, and it was like ‘Oh wow, you can actually say stuff.’ So I started writing songs. When I left Berkley I joined a rock ‘n’ roll band in Ottawa where I had grown up, made up of a bunch of folkies that I knew, and we all were writing songs at that point, and that’s when I really started taking it seriously. It kinda grew from there’

– So that was the beginning of the solo career?

Yeah, except I did it with my wife at the time. At first I wasn’t really on the road – we were on such a small circuit, that it didn’t qualify as on the road. There were clubs in Ottawa, Toronto and Montreal that I could play and the occasional folk festival, and in the early says that’s what I did. I was in bands for the second half of the sixties but had started to do solo stuff in the latter part of the 60s. ’69 was a fairly busy year for me as a solo artist, and that’s when the first solo album was recorded. In the spring of ’70, I bought my first truck, I was started to get paid for gigs so I had some money. It cost three thousand dollars, which was a big deal at the time. And we put a camper on the back of it, and spent the next five years driving back and forth across the country, staying with my in-laws or my parents during the winter and hitting the road again as soon as it warmed up. So for 7 or 8 months out of each year we’d be on the road.

– Was there a sense of the emerging Canadian sound?

There WAS an emerging Canadian sound, but there wasn’t really a sense of it. People started thinking about it after the fact.

– It must have really pissed off the Americans.

That Canada had all the best song writers? I don’t think anyone thought about it – in those days you didn’t say you were from Canada – most Canadians were embarrassed about Canada. Most Canadians didn’t know that Joni Mitchell was Canadian, or that Neil Young was Canadian. You’d say it to people and they’d go ‘What? Nah, that’s bullshit!’ It’s like ‘Can any good thing come out of Nazareth???’ Same thing.

There were a lot of us around that time who thought this was a bad thing who were right behind Joni, Neil and Gordon Lightfoot, who was the first to opt to stay in Canada rather than to move to the US. It was a cliche of Canadian culture that in order to be accepted by Canadians you had to prove yourself somewhere else first – you could do it in England or the US, but not in Canada.

But there was kind of a wave of nationalism that we were all affected by at the time that said it shouldn’t be that way, so I just thought I’m going to build up whatever audience I can in Canada before I think about going anywhere else, and then we’ll see where it goes. Over the next ten years – it took about that long to build a strong national audience, but by the end of the 70s I did have that, and I was also starting to work outside of Canada, a little. But hardly in the states at all – it was Italy and Japan at first. The states did really start to get interested in me until ’83 when Stealing Fire came out, when we started to do national tours.

– Didn’t you get some adverse press for Rocket Launcher?

No, it got no adverse press, it got nothing but positive response – it blew my mind! The Religious Right to my mind said nothing about it. I got the odd letter from somebody who were disappointed in it. One woman I remembered writing saying how could I write an anti-American song like this – her husband was a jet pilot and didn’t I know what awful things the Russians were doing in Afghanistan? Well yeah I do, but it doesn’t excuse what you guys are doing in Guatemala, and it’s not your husband who’s guilty, it’s other people.

I got the occasional letter like that, but what I also got was a huge amount of air-play for that song, which I hadn’t really had before – the one exception being Wondering Where The Lions Are which got played in the US as well as Canada. WWTLA was the first song I’d had that got big time national air-play in Canada and it got on the Billboard chart in the US. But whereas it was the start of something in the Canada, in the sense that the next few records I put out also got a lot of air-play, in the States that didn’t happen, so with Rocket Launcher it was like starting all over again. And that time it did take, and it’s been progressively better since then.

– How did your music develop through the 70s?

The finger-picking that I’d learned to do was based on Mississippi John Hurt and Manse Lipscomb, mainly, and other old blues guys like that, but I’d also learned how to play more complex chords. When I went to Berkley I went majoring in composition, with guitar as my instrument and I had this notion that I’d be a jazz musician – I hadn’t thought about it one way or the other, but that seemed like the thing you do when you went to Berkley! And then I realised part way along that I wasn’t prepared to do the amount of work, and I wasn’t interested enough in jazz harmonies per se to pursue it the way they were teaching it. But I still loved jazz and continue to love jazz, and whenever there’s an opportunity jazz creeps into the music – more now than ever, partly to do with increasing command of the instrument over the years, and partly to do with exploring options as a writer.

– Did you continue to study?

I didn’t study formally in anyway – I taught myself this and that. But I listened to a lot of stuff – you mentioned the world music thing – through the late 60s and into the 70s I was listening to music of every culture that I could get my hands on. I was particularly infatuated with European Medieval and Renaissance music – you can hear that in the records. I was also listening to African records, Tibetan Ritual music. I guess I got started on that track at Berkley because a lot of the jazz players were interested in Arabic music. That interest in Eastern music was prevailing in the jazz scene at the time and I got totally captivated by it.

So the guitar style was partly having started with a blues style that featured alternating bass with a melody over the top or a droning bass with licks over the top, the melodies and the licks got more complicated, and the harmonies never were as simple as blues harmonies so. So on top of that would be a song like Joy Will Find A Way, where the guitar part is an attempt at duplicating an Ethiopian thumb harp piece that I had on a record – it’s not the same notes, but an attempt to get that feel into it. I found that a lot of African folk music suited adaptation to finger picking guitar, which wasn’t lost on the Africans either, but I hadn’t heard African guitar music then. It was obvious to me that you could take these complimentary drum and xylophone type instruments and translate that music onto the guitar, and that became part of the style and then everything I heard that I like really.

And then in the 70s I discovered Reggae and then Punk came along and revitalised rock ‘n’ roll for me and so then I started getting those elements in there to.

– Was electric guitar an anathema – with prog rock etc.?

I used it a bit – all through the 70s there was also the Stones, don’t forget, so there was goo guitar around of the sort that I related to as roots based. And there was good jazz guitar, although there was a period in there where I didn’t listen to much rock or jazz – I completely missed David Bowie, for instance, until Heroes in the late 70s, then I went back and discovered the rest of what he’d done. Then I started to look into rock music again. Yeah, I missed a lot, but I also gained something in the freedom I had from that influence at that particular time. When the influence came around it was affecting me as a more developed artist.

– So the addition of electric stuff happened around Humans, or Inner City Front…?

Inner City Front was really the big one. There’s electric guitar on many of the earlier albums, but it didn’t start to take over until I was playing with heavier bands with more drums and more emphasis on rhythm, and then it was an irresistible pressure to pick up the electric guitar – to hear myself on stage for one thing – but also to keep up in intensity with the other guys. There was a big learning process in there. on Inner City Front I got away with it, but there a lot of learning in front of people going on. I was applying the same techniques to the electric as I used on the acoustic, but there’s a big difference in touch and it took some time to kind of get the feel for it.

– Was there a parallel between the music and lyrics in that development?

The earliest album that has a real noticeable amount of electric guitar on it is Night Vision, which is also a dark kind of record and I hadn’t thought about it but I guess that’s true, it does contribute to it, though unconsciously – I must contribute to what I was doing. The choice wasn’t unconscious the connection was’

The tone of the albums really changes with Humans, which also coincides with my divorce, and the end of a decade and a point in my life that was partly triggered by the divorce and partly not where I spent a lot of time looking at how my inner being related to the big picture, the cosmic picture, and it was time to include other people in that search for an understanding of relationship. To put it in simple terms, as a christian if you’re gonna love your fellow mankind you gotta know who they are, you can’t love them in the abstract. So it was time to kind of be among humans. It started with the album humans and the songs there come from those first travels in Japan, and Italy – the first ventures outside of North America, and the greater understanding of human interaction on mass which translates into politics, and that carried through into inner city front, and all through the 80s.

– Your one of the few artists who was around in the 80s, when all the world’s singer songwriters went electric, who has no embarrassing period…

I was pretty careful, but I look back on certain of those things with a little embarrassment, but only a little – more the live gigs that the records cos there were more chances taken on stage than in the studios.

– Influences –

The Clash, Bob Marley that whole new wave thing had a broad non-specific effect but I remember thinking on Trouble With Normal, on Tropic Moon, and I could figure out how to get the right feel, so I remember thinking, ‘what would the Clash do with this?’ so I did what the Clash would’ve done with it, that was a conscious decision in the studio – it doesn’t sound very much like the Clash at all, but you can hear that mental process’ Bob Dylan was still an influence – Blood On The Tracks – he hadn’t had much of an influence on me for years and then Blood On The Tracks came out and that was a big album for me. Life in general – at that point I was starting to write life and looking outward’

– But there’s a musical sophistication that goes beyond those influences, more of a Peter Gabriel kind of vibe –

That has partly to do with the producers on that album, although I listened to a little Peter Gabriel, though I don’t think it was as much Peter Gabriel as listening to the same things that he was listening to and translating them. The producers, John Goldsmith and Kerry Crawford, who worked on World Of Wonders and Big Circumstance – their understanding of album production was bigger in scope than I was used to working with, and that’s one of the reasons why I was interested in them. So they got bigger sounds, and used more instruments and tried out more ideas, the music lent itself to that. At that point I’d been in Central America, and been to the Caribbean a bunch of times and I had more direct influence from those cultures – see how I miss you, down here tonight, world of wonders – on that song the imagery is all European, but the music is Afro-Caribbean.

– Influence of the Stick?

That had something to do with it as well. That was the thing that interested to me about the Stick. I was excited when I discovered that I knew someone who played it. With Hugh Marsh I’d explored the possibilities with Violin and Guitar, then Hugh’s brother Ferg (Fergus Jemison Marsh), turned out to be this incredible Stick player who was very Tony Levin influenced with the bass strings, but added on all this treble stuff that you don’t hear Tony Levin doing, and it seemed to me that there would be incredible textural possibilities with that part of the stick and guitar. So that became a big deal.

During the period that I was writing the material for Stealing Fire, I’d rented a little office space that I’d go to to practice and or write each day, and I had a little drum machine so I’d set up drum rhythms, and I have the lyrics and I’d be pulling at the lyric and the rhythms and that would spawn the guitar parts, and I got Ferg coming over and work on Stick parts that would go with the guitar parts, and then I’d modify the guitar parts if he had something better than I did. So the presence of the stick was in there early on in the process of building up to ‘Stealing Fire’.

– There are strong polyrhythmic possibilities with the Stick –

and then when you start adding drums to that the trick is to get people to start leaving things out because you can get so many things going at once.

– Guitars – who were you listening to?

I don’t think I was really listening to guitar players much through there. Since about 1960 I haven’t really tried to learn anything off a record in a ‘OK, how he’s doing this’ kind of way. I get influenced by the feel of things and I sort of take what my ear will grasp and then I mess with it, so the learning process has been slow, but also kind of less conspicuously influenced by any one person that it might other wise has been.

– And that helped to maintain originality?

It has had that effect, I don’t think I did it on purpose that was, it’s just my nature to do things that way. I would hear things I like, and any time I heard one I’d either find a way to do it my way or it would just become a kind of general influence – there were lots of people, Mark Knopfler was the most conspicuous fingerstyle electric player around, but I was always sort of slightly uncomfortable with that, even though I really liked his records, everyone would be telling me that I played like Mark Knopfler, once I started playing electric guitar, and it kind of was a little irritating, so I made a conscious effort where possible not to sound like Mark Knopfler – there was already one of him and we didn’t need another one.

– You started fingerpicking on the electric before Knoplfer, what lead to that? Naïvité’?

There was no question in my mind of ever picking up a pick – there was no reason to. I’d played electric guitar when I was in rock bands in the 60s, and I’d had lots of experience playing electric guitar with a pick. But through the 70s I’d developed enough facility with the guitar that it just seemed like OK now how do I apply this to this other instrument, and by the end of the 80s I’d sort of almost learned how to do it!!

– It gave you a unique sound, and a continuity between the electric and acoustic.

They’re not polls apart

– sometimes it’s pretty hard to tell which you’re playing.

yeah, depending on which guitar I’m using – the National Resophonic that I’ve got is an electric guitar but I’ve got it strung with acoustic gauge strings and it has this chunky sound that has much of the attack of an acoustic.

– What electrics were you using in the 80s?

I had a couple of Strats, and a couple of hand made flying Vs, made by Emory Deyong, in Canada. They were really nice guitars, with humbucking pickups, but I’ve always had a problem playing Gibson style electrics cos the necks are to flexible and I’d always bend them out of tune, I grab them too hard, whereas Fenders, or anything with a Fender feel didn’t present that problem so I tended to lean that way. Also the attack on Fenders in more finger friendly, more like the acoustic.

– A kind of natural compression to the sound?

yeah, so it suited’ it easy to overplay an electric guitar when you’re used to an acoustic, whether it’s fingers or a pick. One of the most flagrant historic examples of that is Django Reinhard – when you listen to his records on electric guitar they sound horrible next to the genius tone, not to mention the content of his acoustic playing. He’s whacking the shit out of the electric and it hurts! And I did the same thing -everybody that switches, has to overcome that same tendency which was made easier on certain guitars than on others.

– After the darkness of Big Circumstance, you came back with a far more commercial album in Nothing But A Burning – a shift to new country?

The term new country got invented after we made that album, but the conscious effort made in those songs was definitely a shift. I’d had this big dry spell and at the end of the 80s, from the middle of 88 to the end of 89 I didn’t write anything,

– was that scary?

It was very scary, it was sort of like well OK, either I’ve got to think of some drastic thing to do or I’ve got to go and learn a new trade! So I decided to declare myself on sabbatical, I was gonna take 1990 off, which I did, and I just announced to the world that I was going to have no public involvement with anything, and I more or less did that. And within a week of having started on my sabbatical I started writing, and I wrote Child Of the Wind, and the songs started coming that ended up making up ‘Nothing But a Burning Light’.

But there’d been this big clearing of the slate before that, like the whole 80s was cancelled. The thing that I’d realised during that dry period was that I’d be looking around at songs and I noticed that I had no virtually no songs that someone who was an untrained guitar player could sit down and make work, and I thought that was kind of a lack, so I deliberately made an effort to write songs that you didn’t have to play like I do to make them sound good, you could just strum the chords and they’d still work. So Child of the Wind was like that, and most of the other song on NBABL fit that description. That was on purpose, that had the effect that it wasn’t an attempt to make the songs commercial, it was to make the accessible to someone that wanted to have fun playing them. And that kind of carried over into Dart to the Heart, and then I kinda dropped it – I got bored with that!

– Any label pressure?

No – well, record companies like radio air-play – but nothing that affected the content of the songs, or even really the way we recorded them. The choice of T-Bone Burnett to produce those records was a process that involved the record company, but we had a list of people and he was on everybody’s list. The sound of those records owes everything to T-Bone, and to the particular to the writing of the songs that set that up.

– Burning Light is an amazing sounding album

Nothing But A Burning Light came out really well. Dart To The Heart we didn’t get as lucky on, although there’s still a lot that I really like about that. But NBABL was one of those instances where everything falls together exactly right. It was such a great band on there – Keltner and Michael Been, Edgar Meyer and Booker T.

– Two albums with T-Bone on the major.

..and the Christmas album which was done sort of in between, which I produced though I owe a lot to T-Bone for that, for the inspiration of his attitude towards production more than any of the technical stuff. I guess it was the same as my process of learning from guitar players, I didn’t study what he did, but I picked up an understanding from him of how to focus on the essence of a song without screwing it up in the process of adding instruments to it. there are many many ways that you can mess with a song in the studio so there’s something very important about uncovering that essence and keeping it in the forefront.

– Was that a chance to re-indulge your love of folk music?

Well, in a way.. circumstantially I guess’ The Christmas album was something I’d wanted to do for 20 years because I’d loved that music and thought I could do something with it, but it took that long to get somebody to pay for it. We were doing these radio shows out of New York, we did 5 in the end, which became the Columbia Records Radio Hour, which became a monthly show that they did, I ended up doing all the Christmas ones.

– And you duetted with Lou Reed on Cry Of A Tiny Babe????

I know, it amazes me too – you should have been there when it happened. We’d rehearsed it but he was reading the lyrics off. There we were playing the song, and it came time for his verse and that’s what he did, and I just started laughing as you can probably hear on the ensuing chorus.

– New York was a favourite of yours?

Yeah that was a great album – I don’t really know the body of Lou’s work’ you know who else I really liked through that period was Laurie Anderson, or course they’re now a pair which is pretty interesting. She did some marvellous stuff. I don’t go to many shows, especially big shows, but I remember going to see her at Massey Hall in Toronto and it was maybe the best show I’ve ever seen, for sheer entertainment and content’

– now your on Rykodisc – it sounds like your back in a love affair with the guitar…

It’s what came out of the experiment – it starts with Dart, or maybe even Burning Light. It’s like I said, but the end of the 80s I’d finally learned what to do with an electric guitar, and you can start to hear that on the records, and it continues, I’m still learning all the time – the more I learn, the more I want to do with it, though the new album doesn’t feature that much electric, there’s a couple of prominent bits, but the Charity of Night features some extended leads and stuff. It’s the first time I’ve felt confident enough to allow myself to do the jazz part of the record – I’d always imported other people to do that, you get John Goldsmith on keyboards, or Hugh Marsh on violin adding the jazz into it, but as of the Charity of Night it was time for me to try and do some of it myself, though on the new album it’s not so much on the electric but the two instrumentals have a lot of improvising in them. I’m just letting myself play – we’ll see what happens when we put the band together to tour’

– And live? At Greenbelt the guitar playing was really front and centre…

That’s always been part of the live shows – Dialogue With The Devil, although I’m playing different thing in the solo part of it, it’s basically the same way I was doing it in 1974. To some extent those little lead things have always been in the shows, more so than on any of the records, and with the band shows there’s always been more electric guitar leads, until now when it seems to be evening out a bit. It’s fun to play, you know? It’s partly getting older and allowing myself more freedom. I’ve always had this built in limitation of things supposed to be a certain way, I’ve a limited concept of how things can be and how stretchy you can make things, and over the years that’s gotten a lot looser.

– The record sounds unfettered. Fun, passionate and full of energy.

There wasn’t much restraint – the restraints on me are my technical ability more than anything, and I suppose ones technical ability limits to some degree what you can imagine, at least in my case it does! It doesn’t stop at the same place, but you hear things projected from what you know how to do.

– your guitar now is a Linda Manzer, right?

I had a Larivee – I had the first cutaway guitar that Larivee ever made. Larivee was the first Canadian guitar maker to work with steel string guitars, and he developed a whole style of guitar making that owed nothing to Martin or Gibson, having a different concept of bracing, ‘n’ all that. And Linda along with a couple of other people was one of Larivee’s apprentices for a while – there were three of four of them who were spawns of the original Larivee thing, only Larivee has moved into more a shop thing, with helpers – not a factory as such, but more like that than it was. Linda continued to make guitars on her own.

I had two Larivee guitars, and a David Wren, who was another Larivee apprentice. I had two Wrens, one got destroyed in a fire, at a rehearsal space, which was right before one of the tours of Italy, so I had to play electric guitar – my telecaster was all I had left, and the Italians were really pissed at that, and were yelling out ‘acoustica, acoustica!!’ They didn’t want to hear me playing electric at all, and didn’t believe that my guitar had been burnt – they thought I was putting one over on them.

Anyway, I ended up moving from that to a Manzer. I’d experimented with a few commercial guitars that people were trying to get me to use, and I didn’t like any of them – that was in 86/87. The guitar that Linda made me then I had until the beginning of this year and I traded it back to her for a new one with slightly different characteristics. It was a particularly deep bodied guitar with a cedar top, slightly wider than average neck to make room for finger-picking. When I got it that’s what I wanted, but over the years as I started switching back and forth between electric and acoustic more often, I started wanting my acoustic strings to be closer together so it wasn’t such an adjustment moving back and forth. I found to that I developed a problem over the Charity of Night tour I started getting a problem with my right hand fingers, and what had happened is that because of the extra body depth – we’re only talking about a 1/2 inch but with a guitar that’s significant – the top corner of the guitar was pressing in the nerves in my forearm and over the 10 years that I’d played the guitar it had started to cause problems with the nerves in my arm. So I approached Linda about getting another one from her and she makes a kind of guitar that’s sort of wedge shaped – narrower on the bass side. You sacrifice some bottom end tone, acoustically, but no-one listens to guitars acoustically any more live anyway – very few people even know how to mic one anymore’ The wedge shaped one is not extra deep, mainly because survival is more important than the bass end! That’s what I used at Greenbelt – it’s slight, and not really noticeable to the casual observer, but it does have enough of a slope that it doesn’t put pressure on that particular spot. I knew this from playing the Dobro which has a very thin body and I wasn’t having any trouble playing that so duh! Make the connection, it’s obvious! But so ended up with the new Manzer, which I really love. As I said, it sacrifices a slight amount of bass tone acoustically, electrically, with the fishman pickup that’s in it, it sounds as good as any other guitar with a Fishman. Just the latest generation of piezo. It’s got a really nice neck – it’s a beautiful guitar to play.

– Mic and line in the studio?

Normally I would just mic it – we probably did some of it plugged in, but we never used it, it’s kind of more for safety – if we get a little noise on the mic, or we have to punch in…

But I don’t really like the sound of it plugged in when you don’t have to have it – it’s there live because there’s no other way, but the new Manzer is not what appears on the new album – that’s a Collings that I have that I’ve had for three years. It’s the one that like D28, big body. You hear that on the Charity of Night and on Breakfast in New Orleans, Dinner in Timbuktu, because the new Manzer was still too green – it hadn’t opened up yet’

– Electrics on the album?

On Blueberry Hill, it’s a black and cheesy Charvel Surfcaster, And a Strat that a friend gave me that she’d had lying around is doing a lot of the leads of the album.

– which artists have you seen recently that class as ‘ones to watch’?

Ani Defranco well enough known at this point that she’s not really one to watch unless you haven’t heard her yet in which case you’d better! But she’s to me the best thing happening now, in terms of acoustic style songwriters. And Kelly Joe Phelps is running right up there behind her. They’re both completely original really interesting players playing very different styles of music, but very distinctive in their approaches. For guitar players, Bill Frisell – he’s somebody that I would go out of my way to see live, and Marc Ribot – the Cubanos Postisos Record – that’s an incredible record. I saw him play in New York at one of those weird avant garde gigs and he was excellent – those are the kind of things that interest me. James Blood Ulmer is someone else that interests me greatly, and has done since the 80s.

– are you influenced by the avante garde?

I like stuff that’s out on the edge, I’ve always liked that. I’ve never seen myself as being there, but I’ve always wanted to be.

– Any plans to work with Jonatha Brooke again?

I’d love to, but there’s no plans to at the moment’ She’s a fantastic writer and singer and a great person. She’s someone who uses a lot of different tunings but really uses them interestingly and doesn’t just play the same thing from tuning to tuning. She’s got a great sense of sonority.

To The Left Of The Mainstream – new music recommendations

I’ve written before about the need for filtering in the online music world – there’s just too much music and not enough time to leave it all to chance. As Jeff Schmidt just expressed it on twitter – “curation is vital”.

Which is why I’ve just started To The Left Of The Mainstream – a twitter-based music recommendation feed. I’ll post at least once a day, sometimes more, with links to great artists, with the proviso that all the sites will provide full track on demand streaming tracks or downloads. They’ll mainly be from Myspace, last.fm and Reverb Nation…

So if you’re on twitter (you should be), you can ‘follow’ TTLOTM on there, or just click the link and then grab the RSS feed to follow it in google reader or safari or wherever. I’m sure you’ll find loads of great new music through it.

Stylistically, it’ll run the gamut from singer/songwriters to ambient music, rock bands to chamber works, electronica to nu-jazz. All the kinds of things I love. There’ll be no ‘buy-ons’, as it’s only going to be of any value at all if the sole criteria is quality…

That doesn’t mean I’m not taking recommendations – make those in the comments below please (rule #325, you can’t recommend yourself! ;o)

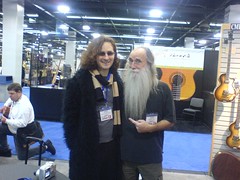

Lee Sklar interview from Bassist Mag, Oct 99

One of my favourite things about going out to NAMM each January is getting to see Lee Sklar – if you’re a bass player you obviously already know who he is. If you’re not a bassist, you might recognise Lee as the guy that played bass with James Taylor and Phil Collins who looks like the Farside version of God.

One of my favourite things about going out to NAMM each January is getting to see Lee Sklar – if you’re a bass player you obviously already know who he is. If you’re not a bassist, you might recognise Lee as the guy that played bass with James Taylor and Phil Collins who looks like the Farside version of God.

He’s a bona fide bass legend, has defined how the rest of us approach playing with singer/songwriters, but has covered so many other styles, including playing on Billy Cobham’s classic fusion record, Spectrum.

Interviewing Lee back in 99 was a real pleasure, and an honour, and since then we’ve become friends, and always catch up for a chat a NAMM. He’s on tour with Toto at the moment – if you go and see them play and get to say hi after the show, please pass on my best!

here’s the interview – enjoy!

—o0o—

Lee Sklar Interview

(Reproduced from the October 1999 issue of Bassist Magazine)

Few faces are as instantly recognisable within the bass world as Lee Sklar. The same is definitely true of his playing. With more than 30 years and 2000 albums behind him, Lee’s sound has graced more hit records than almost anyone.

Aside from being a hired gun, Lee is best known for his long standing musical relationships with Phil Collins and James Taylor. Indeed, it was the gig with James that proved to be Lee’s ticket into music full time back in the late 60s.

“I was in a lot of local bands in LA, including a band called Wulfgang,” recalls Lee. “James auditioned as the singer but wasn’t what we were looking for – we needed someone somewhere between Sam ‘n’ Dave and Robert Plant! James blew me away but just wasn’t right.

“About a year later, James asked me to do a gig, which I immediately agreed to. We did two gigs at one venue – the first was before ‘Fire and Rain’ and the place was so empty you could drive a truck through it. At the second show, the place was packed, and we knew we were onto something! So a gig which initially looked like being one or two shows ended up being 20 years.”

So was it working with James that opened the door to session work?

“Yeah. It’s funny, I’ve always considered myself a band guy. I was an art student in college and I still think I’m a better sculpture than musician. Music was just a weekend hobby – I had no intention of becoming a studio musician. I was really shocked when I started getting calls to play on people’s records.”

Unlike many bassists, it’s impossible to label the one kind of music that you get called for – your CV is so diverse. How did that come about?

“I don’t really know – I feel really fortunate to have just got the calls! I guess that once I came to the realisation that I was a studio musician, I discovered that the most essential aspect is having really wide ears, embracing all styles.”

Has that always been your approach?

“Not at all! I started playing classical piano at four years old and was still a complete classical music snob when I started studying upright bass – all orchestral stuff. I wasn’t into Elvis or the Beach Boys – I was into Gershwin and Copeland. It was a different world. Then the first time I heard the Beatles’I was an usher at the Hollywood Bowl the first time they played there – Paul changed my life! (laughs)

“When I got into the studio scene, I found myself getting all kinds of calls. One minute I’m doing Helen Reddy’s ‘I Am Woman’, and the next thing I know I’m doing ‘Spectrum’ with Billy Cobham. The calls would come in and I’d just look at everything as a challenge.

Have you ever turned down a session?

“Occasionally – I’ve had a huge amount of wrist injuries, so I can’t play thumb-popping (slap) style – I don’t have the dexterity to deal with it. So when people call me to do that, I put them in touch with friends I have – I’d rather see other guys working, and I’ll just come hang out.

“I also don’t play upright anymore. I was doing a project where I was using a Washburn 5 string fretless to get an upright sound, but they had a couple of songs where they wanted real upright and I said ‘call Patitucci’ – it was when he was still living in LA – and I went down and hung out at the sessions with John.

“I’ve always tried to understand my limitations so I try to find out ahead of time what they want on the session. The one main thing I’ve cultivated is a real sensitivity to singer/songwriters. I know how to accompany, and how to listen to a person breathe to hear where the down beat is – to never try to lead them. I’m really comfortable on that seat – I’ve never considered myself a virtuoso. It’s like going to the NAMM show and listening to all the guys with the monstrous chops – I’ve never considered myself that. I’m happy when people say I’m ‘king of the whole note’ – I really value that position as a bass player. I’ve done fusion, but I like being an accompanist.”

From a listener’s point of view, it sounds like you spot the holes, and never play across the vocal?

“I think it just requires listening and one of the problems that a lot of players have is that they don’t listen. Don’t get me wrong, I admire the tenacity that it takes to develop NAMM show chops – you see all these guys that have these different gifts and it’s fantastic. But I’m just one of these people that if I’m doing a recording and they ask for a bass solo I say I’d rather hear another song in that space, and I’ve heard some of the greatest soloists in the world play. I can enjoy it for a bit but I’m really a song person – maybe an element of it is laziness on my part. I grew up in an era where you were hired as an accompanist, even if you were doing a metal project. I really believe in the song.”

I assume that that sets producers at ease?

“Not only the producer, but I often get hired because the artist feels like they’re going to be comfortable with the extra room to breath. Guys get so used to ‘time’ that they don’t really understand that you can have a beautiful pause before a verse, because you’re human! Don’t do all your training with a metronome, try to understand what it is to really feel a song. Don’t be afraid to leave that kind of space. That’s what I’ve always liked about Asian thinking, the importance of space, allowing things not to be there.

“I did a clinic at the Bass Centre in LA a few years ago, and it scared the crap out of me. I only agreed to it as a non-playing clinic – most of the guys there were sleeping with their basses and waking up and playing them – that’s what I was like at that age, too. Anyway, they got to talking about how boring it must be to play country cos there’s not much going on. And I said a whole note is much more difficult to do than 32nd notes, which only demands proficiency. If someone gives you one note to do in a bar, there’s a whole lot more responsibility – where do you drop that note? Do you put a little vibrato on it? Which string do you play it on for tonal quality? When do you lift off? Do you mute it with your hand? They were all looking at me saying ‘geez we just thought it was boring!’

After so many tours and albums, do you still have any unfulfilled ambitions?

“I would like to get back and start sculpting again. I haven’t done it for a long time now, just because the music has occupied such a large part of my life. I’m going to be 52 years old this year, and you’d think at this point in my life that maybe things will start to slow down but I’m still as busy as ever! I’ve been working with artists from Mexico, Japan, Thailand and France; I’m musical director on a TV show, I’ve got sessions coming up with Barbra Streisand. It’s amazing to me that I’m still getting all these calls. My ambition is just to keep doing what I do. I just really enjoy getting up and going to work and playing with guys that I like playing with. That and enjoying my home life – my family, my pets, my garden, building cars. I feel like a big pie, and music is a slice of the pie but not the whole pie. It impacts everything else I do, but I don’t have to be playing every day to feel I’m a valuable person.”

In Defense Of REAL Musicians!

After 30 years in the industry, having seen recording technology blossom from the days when a four track was state of the art to what we have now – how has that changed it for players like yourself?

“Firstly, I’m all in favour of technology – I don’t want to be living in the stone age – but one of the biggest problems with technology is that it’s become so good that it’s allowed people into this business that should never have been in it. With Pro-Tools and such like, you’ve got singers that can’t sing to save their lives and engineers whose whole careers are spent tuning bad singers. You’ve got a drummer with no time, so you move the beat. As far as I’m concerned if the guy doesn’t swing, fire him – let him serve french fries in McDonald’s, but don’t let him get in a studio, because there are too many great players trying to get into that seat. That aspect of technology I find really disconcerting.

“Every once in a while I work on things and I feel like I’m in the old days. We got so used to that – going into sessions with Jim Gordon, or Jim Keltner and the pocket was so strong! Everything was based on ensemble playing, whereas nowadays, at least half the work I do, I’m just overdubbing to sequenced bass and they want it to feel natural, but you’re already handcuffed by the fact that this was done to a sequencer and they want you to make it breath a little bit and I think: why don’t they just put a rhythm section together and do this???? People are afraid – they want to keep as much control and money as they can, and are afraid to let a bunch of guys come in and actually play something. I’ve worked with people and we’ve had to make their records that way and suddenly we’ll do a gig and the first time the band plays the song it’s a hundred times better than the record and they’re wondering why! It’s because we’re all putting personality into the tunes.”

Lee’s gear

Working in such diverse situations requires quite a few different tools – here’s a list of the current Sklar arsenal [current as of Oct 99!] –

1. A Fender(ish) 4 string bass – “It has Charvel alder body, two EMG P-Bass pickups in Jazz position, but reversed, a Badass Bridge, a Hipshot D-Tuner, and mandolin fretwork.”

2 Dingwall 5-string “bitchin’!”

3 Yamaha TRB5 fretless

4 Washburn AB45(s?) acoustic fretless

5 Tubeworks DI

6 Euphonic Audio 2×8″ and 2×10″ speaker cabs.

7 Walter Woods amp

8 GK 1200 combo amp

9 Boss Octave pedal (‘my rack consists of this one pedal!’)

10 GHS Super Steel Strings 40-102.

That’s a fair amount of gear, but as the man says – “It’s still the same old me at the helm so what the hell!?”

Spinnin' around…

Yesterday was the closest I’ve come to being killed for a very long time. Driving back from a lovely trip to Kitchener, Canada (more on that in a moment), Lo. and I hit a patch of black ice in the road, just at a point when the wind was blowing hard enough to knock us and the cars in front of and behind us into a spin – the car in front of us spun off the road, I turned to go around him and the car spun across the road, did 180 degrees and we ended up on the central reservation facing the wrong way with more cars and SUVs spinning off the road around us. The spin itself was scary, but we didn’t hit anything, and the central reservation brought us to a fairly quick halt. However, the feeling of watching other cars spin, knowing that if one of them came in your direction it would very possibly kill you – given that we were facing the direction they were coming, so it would’ve effectively been a head-on collision – is quite the most gut churningly horrible feeling I’ve had for a very very long time.

And after that, when the road cleared a little and we’d got turned round and on our way again, the next 50 miles back to where we’re staying was the most stressful nastiest drive of my life, every little movement of the car felt like we were going to spin again, every bridge felt like it was covered in ice, and on a couple of occasions we did slide a little, and my stomach knotted even further. I’ve never ever been so happy to step out of a car as I was when we got back.

So we’re not dead, and very thankful to be alive and in one piece, and to not even have to report a smashed up car to the rental firm (we had fully-everything insurance anyway, and I suggested that they check the wheel alignment, given that the wheels took more of a jolt when we hit the reservation than anything else…)

The reason we were in Kitchener in the first place was to go to a gig by Rob Szabo and Steve Strongman, two fantastic singer/songwriters, with very different but complimentary styles. They traded songs off one another, backed eachother up, and generally made a fantastic singer-songwriter-y noise for a couple of hours. Marvellous marvellous music. Definitely worth checking out both of them.

Anyway, happy christmas, bloglings, thanks for bothering to read this stuff through the year, I hope it’s been entertaining and informative. Here’s to a blogalicious, gigtastic 2008!

busy busy busy

It’s all go here!

We’ll start with last weekend – two gigs, Saturday/Sunday.

Saturday’s was a gig with Lobelia in Brighton at the Sanctuary Cafe, opening for MAP – that’s and Peter Harris – both incredible acoustic guitarists, writers of sublime melodies and fantastic performers. Also on the bill before us was a marvellous singer/songwriter, Conrad Vingoe – as well as having one of the most rock ‘n’ roll names ever (not much chance of that domain name being taken), he writes great songs and has a gorgeous voice. All good. ‘Twas a small crowd, but the venue was intimate and sounded good, the people lovely and a fine time was had by all… I’ll put photos from it up on Flickr soon.

Sunday’s gig was back at Smollensky’s with Luca Sirianni, this time with Sophie Alloway on drums. The gig with Luca is becoming a fairly regular thing, and a whole lot of fun – the chance to play a lot of pop/latin/jazz tunes, do some interesting arrangements, get funky and get paid (a bit). Luca’s a fine guitarist, who does enough ‘dinner jazz’ gigs to know just the right kind of things to play, but also likes to stretch out, improvise and have some fun. It was the first time I’d played with Sophie, and she was a treat to play with – not having come the usual ‘3 years at music school’ route, she plays with the maturity of a player who’s been gigging twice as long as she has, because she learnt on gigs. One of my main gripes with so many drummers is the don’t listen well – they establish a beat and stick with it, instead of letting the grooves grow and expand. Sophie listened really well, and also – crucially – understood the space a drummer has to occupy in a trio. As usual, I hit my stride about half way through the second set, but that’s the price I pay for not playing with drummers often enough…

…Though that’s not the case right now – I’m in the middle of a really fun recording session with Patrick Wood and Roy Dodds – if you saw the last Recycle gig, you’ll know this is a pretty special trio… We spent most of yesterday setting up, but got about 20 minutes of amazing music recorded last night, and will spend much of today on it as well… except the time that I’m teaching – thanks to my going away for Christmas and January to the US, I’m having to fit in as much teaching as possible before I go, partly because lots of students want lessons before I go and partly because I need to earn as much as I can in order to be able to pay my rent, and renew my car tax in january…

in between all that, I’m booking things to do in the US (masterclasses and gigs in California), sorting out my tax return (spending a lot of time buried under piles of receipts) and somewhere this week, I need to fit in a few hours to record some tracks for an italian electronica project that I’ve been meaning to record some stuff for for over a year, and HAVE to have done before Christmas…

Add to that regular trips to the post office to send off CD orders for the new EP and people ordering other stuff as christmas presents, and you’ve got yourself one seriously overworked Stevie.

Roll on Ohio…