It’s no secret that I really love Bandcamp. As a fan and as an artist, a huge part of my music life is spent listening to music, finding new music, buying music and of course selling music – almost all on Bandcamp. But it’s also the mechanism by which I get to email my audience, post updates to my subscribers, share videos and even eBooks. It’s why I can remaster anything at any time, change the price on anything, bundle things together and release everything at HD without having to put it on some nonsense specialist site that charges more for 24bit files.

So, I’m going to a couple of posts about just how and why I love it, starting with my experience as a music listener. I’ll preface this by saying that I’m not going to argue that the music listening experience is tangibly better, at least on the surface, than Spotify or Apple Music – the listener experience of streaming apps, at least as it pertains to finding and listening to music is pretty great (and the presence of acres of classic albums is in stark contrast to the new music focus of Bandcamp). But there’s no economic model there that works for niche music unless you use it to cross promote touring/merch/sales elsewhere/patreon, and they really don’t foreground the relationship between artists and audiences, and that REALLY doesn’t work for me. So I’m going to steer away from doing comparisons with streaming platforms for the most part, if that’s OK…

So let’s jump in with what Bandcamp gives me as a listener. When I first started buying music on Bandcamp, there was no app and the driving USP was HD downloads. With the advent of the app in 2013, Bandcamp added a whole other level of portability to both carrying your Bandcamp collection with you and to discovery. The collection part is pretty simple – everything you’ve bought on Bandcamp is there in the app, and can be streamed. Anything you’ve streamed is cached, so you can also use it on planes/the Underground, and you can either search your own collection to find things or sort the list by date added, a-z, most played or ‘history’ (what you’ve most recently played).

So let’s jump in with what Bandcamp gives me as a listener. When I first started buying music on Bandcamp, there was no app and the driving USP was HD downloads. With the advent of the app in 2013, Bandcamp added a whole other level of portability to both carrying your Bandcamp collection with you and to discovery. The collection part is pretty simple – everything you’ve bought on Bandcamp is there in the app, and can be streamed. Anything you’ve streamed is cached, so you can also use it on planes/the Underground, and you can either search your own collection to find things or sort the list by date added, a-z, most played or ‘history’ (what you’ve most recently played).

For each album, as well as being able to play it, you can access sleeve notes, if the artist has added any, and lyrics, read reviews by other people who’ve bought it, add your own review, browse the rest of the artist’s catalogue, and buy those – for yourself or as gifts for other people. What’s more, your collection is public on the Bandcamp site or in the app via your avatar under any album you’ve bought. So people can browse your record collection as they might when coming to your house, and (this is a really lovely touch) if they buy it after finding it through you, you get a ‘hey! you made something awesome happen!’ email from Bandcamp telling you who bought what. Which is just wonderful, and offers some useful data on just how much internal discovery within the site is worth if you can encourage your listeners to review things and make a bit of a fuss about their Bandcamp collections…

The other pure joy for me of the app is how it handles subscriptions – any time one of the artists I’m subscribed to releases a new album it’s immediately there in the app ready for me to stream, as well as available for HD download. Truth be told, I do a huge amount of my listening these days via the Bandcamp app – the streaming quality is easily good enough not to be distracting, and I just don’t get that much time to hook up my hard drive with my iTunes folder on it to a DAC and speakers… But I cherish that those HD versions are there, for good. They are mine for ever. This isn’t rented access to a bunch of metadata overlaid on a ginormous catalogue by a company lobbying to pay the artists as little as they can possibly get away with.

Instead, it’s a service that values ownership, values connecting listeners with the artists whose music soundtracks our lives, does discovery by a range of mechanisms that subvert the bland top-heaviness of an unfiltered popularity contest, but instead focus on what they describe as ‘high friction sharing’ – sending you an email digest every few days of thing things that your friends have Actually Paid For. Anyway, back to subscriptions. I get to hear from the people I’m subscribed to directly in the app. They can post messages and video and photos to either accompany the releases or just to fill me in on what’s going on, and I can comment on those posts and offer encouragement or join a discussion. It’s a joy to carry these extensive catalogues of work around with me and get to know the work of lesser known artists with the same level of detail and obsession as is often reserved for ‘legendary’ acts.

I spend hundreds of pounds a year on music, the vast majority of it on Bandcamp. A lot of what I buy I could get from a streaming service, but I would then a) not have it to download, and would be paying the company each month for the joy of having potential access to it all, and b) would be guaranteeing that the only artists whose sustainability I was contributing to were the ones I listened to pretty much non-stop, to the exclusion of all others – while my subscription fee also subsidised royalty payments to the world’s richest pop stars.

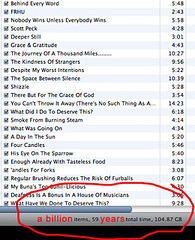

Buying albums is a model based on a bygone era when recorded music came exclusively in a container, limited by the length of audio that would fit on your format of choice. But it did give us a way of pragmatically agreeing on a rough per-listener value for an hour of (repeatable) music. Against that, we can think about how much new music we have time for, and how we go about making sure that the artists we care about get to keep making it. We can release it in ways that seem like a total bargain, but still make us literally hundreds of times more than equivalent interactions on Streaming platforms.

In short, Bandcamp

- Connects me to the artists,

- Gives me the tools to interact with them and with the music in friendly ways,

- Makes it possible to share without forcing adverts on the people I’m sharing it with or making them sign up for an account,

- Gives me the music to archive long term,

- And means I’m on the artists’ mailing list whether or not Bandcamp ever goes supernova (you know that if Spotify ever folds, everything you’ve curated there is gone, right? Renting access is great for convenience, but not so good for digital ecology).

- Provides an open and transparent model that means I KNOW the vast majority of the money I’m paying is going to the artist, and the rest is building the most robust and artist-friendly environment for music sustainability the internet has yet had.

Anyway, the invitation to be a part of the ongoing viability of the music I love by artists I care about, and to discover more of it through the actual taste of the people I follow on there via my fan account (as opposed to a bunch of links they might share to music by their friends or other bands they’re doing promo-swaps with) is an amazing and beautiful thing, and dovetails really well with my own focus on needing music by artists who are trying to make sense of the world as it is, rather than spending my music listening time wallowing in nostalgia in the vague hope that the soundtrack to my teens will stave off the dread of my ever encroaching sense of mortality.

Nope, I want to connect with what people are making now, songs about the world, music inspired by all that we can do and all that we can see. And to make more of it possible. I tweeted a while ago that on Bandcamp, the value proposition is best understood as as ‘buying this album’ but ‘making the next one possible’. Arguments about what music is ‘worth‘ are less interesting than questions about how we make more of the music we care about possible. Tomorrow, I’ll write about what Bandcamp means for me as an artist – the flip side of this equation… Til then, have a listen to some of the music dotted throughout this piece, or have a rummage in my Bandcamp fan collection.